Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a movement disorder that manifests as involuntary, repetitive body movements most often affecting the mouth and face1 and is associated with exposure to antipsychotic drugs (APDs).2-4 Underscoring the importance of screening and assessment is that TD can have a significant impact on the patient's life5 and complicate the management of their underlying mental health disorder.6-9

For some patients, TD may manifest in subtle symptoms.6 Regardless of severity, however, TD can have a disabling impact on patients' lives, affecting their physical, emotional, and social well-being.5

Despite its impact, TD is underdiagnosed and undertreated.10 In the United States, TD affects more than 785,000 patients, and that number is growing.11-12 However, fewer than 15% of these patients are diagnosed, and fewer than 6% of these patients are treated for TD with a vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 (VMAT2) inhibitor.10,13 There is an acute need to better identify and assess TD in patients suffering from this disorder.10

To help recognize and diagnose TD, healthcare providers (HCPs) should routinely screen for abnormal movements in their patients on APDs.14 In a 2020 consensus statement, a panel of experts recommended that screening for TD occur at every clinical encounter with patients taking APDs, whether such visits occur in person or virtually.2,14,15

A brief, semistructured examination is a practical approach to screening for TD movements at every clinical encounter and can be done effectively in any setting.2,14-16

The exam involves looking and listening for signs of abnormal movements. This can be done by observing patients during their visits, listening to their complaints, and talking with their care partners.14

What should a semistructured examination take into account? 14

| • | Patient recognition of abnormal movements |

| • | Visual observation of abnormal movements on examination |

| • | Care partner feedback on abnormal movements |

| • | Patient report of abnormal movements |

| • | Patient complaints about movements being distressful |

During a semistructured exam, activation maneuvers can also be used.17 Activation can help account for the type of distractions that patients may experience in their daily activities, thereby more closely illustrating how their movements may look outside of the office.17 The following examples may help highlight movements in parts of the body where TD is most common18:

| • | Ask patients to hold their arms straight out in front while thinking of 5 words that begin with a particular letter. As the patient focuses on coming up with these 5 words, movements may appear or worsen in the upper extremities and/or the face |

| • | Ask patients to hold their mouths open while sequentially touching their fingers to their thumbs. First, the HCP demonstrates these movements by holding the mouth open, then touching the fingers to the thumb, then combining these instructions. As the patient works to complete the sequential touching, abnormal tongue and facial movements may appear or worsen |

This brief, practical approach to assessing your patients can help identify red flags for TD, which may indicate the need for a more formal Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) assessment.2,14,19

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) recommends conducting structured assessments2

| • | Upon initiation of an APD |

| • | At a minimum of every 6 months in patients at high risk* of TD |

| • | At least every 12 months in other patients taking APDs |

| • | If a new onset or exacerbation of preexisting movements is detected at any visit |

*High-risk patients include those older than 55 years; those with a mood disorder, substance use disorder, intellectual disability, or central nervous system injury; individuals with high cumulative exposure to antipsychotic medications, particularly high-potency dopamine D2 receptor antagonists; those who experience acute dystonic reactions, clinically significant parkinsonism, or akathisia; and women.2

A structured assessment is a more formal and thorough means of screening for, and assessing the severity of, TD.2 The AIMS is the standard instrument for performing a structured exam.2,14,20

The AIMS is a 12-item scale20:

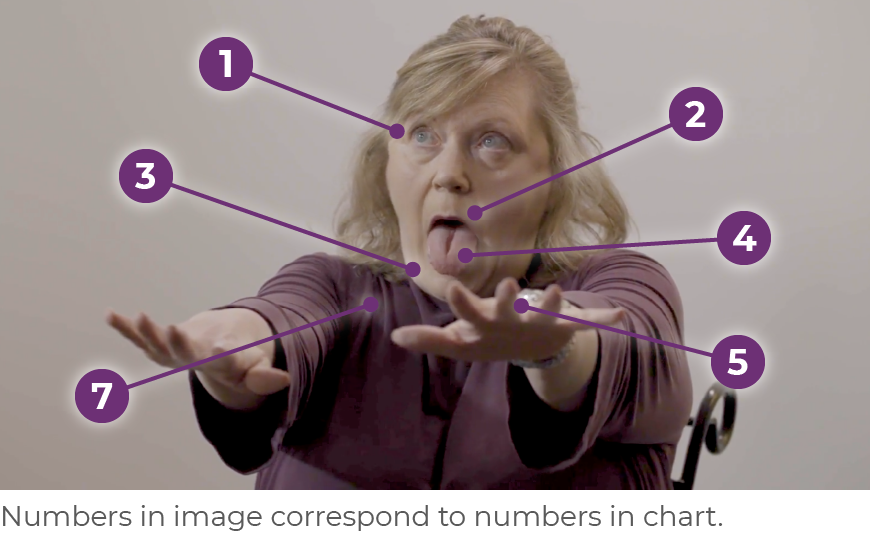

| • | Items 1 through 7 assess the severity of involuntary movements across body regions |

| • | Items 8 through 12 address global severity, patient awareness and distress, and dental status, including whether patients have problems with their teeth or dentures that may interfere with the assessment of abnormal movements |

Telepsychiatry should not stop HCPs from performing an AIMS exam.15,21-23 Assessing 6 of 7 AIMS items can readily be done when patients are seated, where they can be viewed from the shoulders up.15,20,24 With some additional camera positioning, examination of all 7 items in the first section of the AIMS is possible.16

When differentiating between TD and drug-induced parkinsonism (DIP), using a camera to observe the patient walking may allow for the assessment of DIP symptoms, such as slowness or shuffling of gait.16,19,24,25 Rigidity may be suspected if the patient exhibits a lack of arm swing when walking or acknowledges experiencing any stiffness.16,19

Regular screening and assessment of TD in patients on APDs is the standard of care. A semistructured examination for TD should be performed at every visit, including telepsychiatry visits.14 If a red flag is identified, the patient should be formally assessed using the AIMS.2,19,26 In addition to assessing the severity of symptoms, the impact of TD on the patient's daily life should be evaluated.5,14 Regardless of the visit type—in-person or virtual—once TD is diagnosed, treatment should be considered if it has an impact on the patient.2

References

Screening and assessment of tardive dyskinesia (TD) at every visit is an important practice because TD can have an impact on multiple aspects of a patient's life.3-5 Regardless of symptom severity, TD causes disability through its impact on patients' physical, emotional, and social well-being.4,6,7

TD is a drug-induced movement disorder7-9 that classically presents as uncontrollable, repetitive movements of the mouth, tongue, and jaw.10,11 Although orofacial movements are most common, TD movements may also occur in the trunk or extremities.10,11 This disorder is often caused by antipsychotic drugs (APDs), although it can be caused by any dopamine receptor-blocking agent.7-10,12 TD can have a detrimental impact on patients' lives; it is therefore critical to screen and assess for TD,3,4 and once diagnosed, to consider treatment.6,7

With an increase in the use of telepsychiatry, it's important that healthcare providers (HCPs) feel confident in their ability to assess patients in the virtual setting.1,2,13 Fortunately, screening and assessment for TD can be performed effectively in the virtual setting to assess both the severity and the impact of TD.1,2,13 Many of the techniques used to screen and assess during in-person examinations also apply during virtual examinations.1,14

Among all medical specialties, psychiatry has led the way in the use of telemedicine.15 Telepsychiatry expanded during the COVID-19 pandemic and is not expected to return to pre-COVID levels.16,17

The virtual setting is conducive to screening and assessment of TD.1,2,13 In fact, telepsychiatry has numerous benefits over in-person visits, including the ability to observe patients in their own environment, bring family members into the conversation, and reduce no-show rates.18-20 It is unlikely we will return to a time when virtual visits are not part of clinical care17; therefore, it is essential to incorporate a virtual TD assessment into routine clinical practice.1,3,21,22

Screening for and assessing TD at every visit is the standard of care.3,23,24 Performing the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) to assess a patient with suspected or confirmed TD can be easily done during a video visit.1,3,21,22 As with a live visit, the virtual setting allows HCPs to screen their patients for abnormal movements by looking for these movements, listening to care partners, then assessing the movements.1,3 The AIMS exam is an effective tool when performed virtually.23,24

Of note, in clinical trials evaluating treatments for TD, the primary means of assessing patients' movements using the AIMS was accomplished by central raters via video, so using video analyses is not necessarily out of the ordinary.25

HCPs can easily view patients from the chest up during a virtual visit. In fact, assessing 6 of the first 7 AIMS items can readily be done when the patient is seated, with arms extended out in front and the hands hanging relaxed (Figure 2.1).1,2,12,13,26 With some additional camera positioning by the patient or a helper, examination of all of the first 7 items on the AIMS is possible.1,2,12,13,26

Following a virtual diagnosis of TD, a provider should consider initiating treatment.6,7,27

Symptoms of drug-induced parkinsonism (DIP), such as slowness or stiffness, can also be assessed during a virtual visit.19,26 Rigidity may be assessed by asking patients if they experience stiffness. If the patient walks within view of the camera, slowness or shuffling may be observed; additionally, lack of arm swing may indicate rigidity.19,26 If DIP is suspected, an in-person visit may be helpful to confirm the diagnosis before initiating any treatment.1,3

During both an in-person evaluation and a virtual visit, providers should start by explaining what they are doing and why, and demonstrating what they want the patient to do.28,29

To optimize the virtual video-to-video assessment, the patient should have

| • | A helper to assist with camera positioning, directing the camera toward the patient's body during activation maneuvers or while the patient is walking26 |

| - | If no helper is available, instruct the patient to find a location in which to prop up the camera so they do not have to hold it26 |

| • | A straight-backed chair with no arms26 |

| • | Appropriate lighting (ie, having the patient face the light)30 |

| • | Appropriate computer bandwidth to ensure good resolution to see movements30 |

| • | Care partners or family members participate, if available, to see if they have observed any unexpected movements, abnormal movements, or new movements18,19 |

Asking the right questions to uncover the impact of TD and determine its impact is equally critical during a virtual exam.21,22

Telephone-only visits are not ideal, but HCPs still need to screen for abnormal movements and ask targeted questions.1,2,31,32

The HCP should focus on identifying awareness of abnormal movements and their impact.5,21,22 The HCP can instruct the patient to take a video, which the HCP can then review.31,32 If TD is suspected, HCPs should follow up with the patient in person or by a video-to-video call.1,31

Telemedicine is here to stay, and therefore, it is important that psychiatry providers feel confident in screening and assessing for TD movements in the virtual setting.16,17,26 Following these tips can help ensure that providers are maintaining the standard of care in the virtual environment.3

References

Tardive dyskinesia (TD), a movement disorder characterized by involuntary, hyperkinetic movements, is the result of exposure to dopamine receptor-blocking agents, including antipsychotics.1-4 Screening and assessment of TD is so critical because it is underrecognized, can be insidious,1,2,5 and causes disability through its impact on patients' physical, emotional, and social well-being.6

Patients may try to hide—or may not even be aware of—their symptoms or the impact those symptoms may have.7,8 Screening should occur during every visit, regardless of where such visits take place: in person, by video, or over the telephone.9,10

Screening for TD may lead to a diagnosis, at which point an assessment evaluates the severity and impact of the disorder.11,12 The American Psychiatric Association (APA) recommends a vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitor as a first-line treatment for TD that has an impact on the patient, regardless of severity.9

AUSTEDO XR is a VMAT2 inhibitor indicated for the treatment of TD in adults.13 The efficacy and safety of AUSTEDO were studied in 2 pivotal trials, Aim to Reduce Movements in Tardive Dyskinesia (ARM-TD) and Addressing Involuntary Movements in Tardive Dyskinesia (AIM-TD), and a long-term, open-label study of ~3 years, Reducing Involuntary Movements in Participants With Tardive Dyskinesia (RIM-TD).13-16 ARM-TD was a 12-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, flexible-dose trial in which doses were titrated to an individual dose that reduced abnormal movements and was tolerated.15 AIM-TD was a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose trial in which patients were given placebo or AUSTEDO 12 mg, 24 mg, or 36 mg.13,16 RIM-TD was an open-label, long-term maintenance study in patients who successfully completed ARM-TD or AIM-TD. Patients discontinued AUSTEDO for 1 week and then started at a dosage of 12 mg/day; the dosage was titrated for up to 6 weeks. Patients were followed for ~3 years (145 weeks).17

In AIM-TD and ARM-TD, patients were assessed using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) tool.15,16 Interestingly, in an era in which telemedicine is increasingly prevalent, all AIMS score assessments for AIM-TD and ARM-TD were done centrally via video by a group of movement disorder experts who were blinded to the patient treatment arm. The blinding allowed for a systematic evaluation of movements in all patients. These central raters reviewed recorded videos in pairs and had to reach a consensus on the AIMS score.15,16

Results of the 2 pivotal trials indicated that patients had rapid and significant symptom control as measured by changes in their AIMS scores.15,16

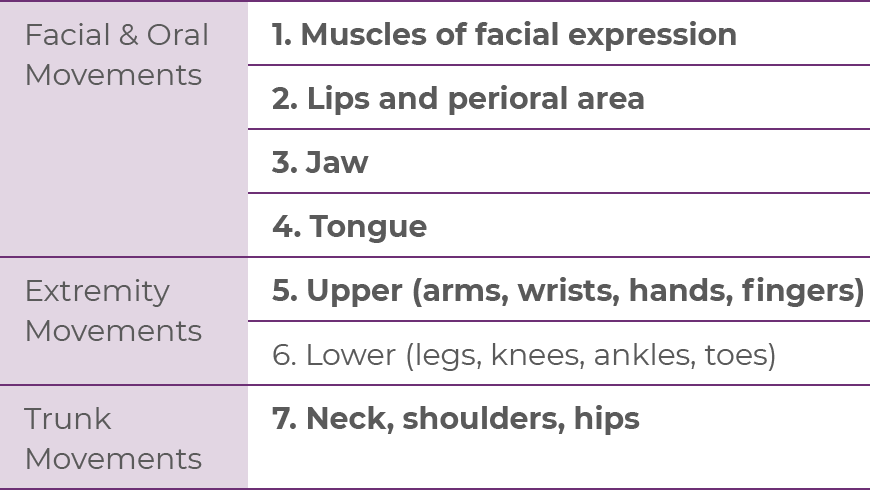

In the AIM-TD study, significant improvement in AIMS total score from baseline (P=0.001) was observed at Week 12 with AUSTEDO 36 mg/day vs placebo (3.3-point reduction vs 1.4-point reduction) (Figure 3.1).13,16 Patients receiving 24 mg/day and 36 mg/day of AUSTEDO saw significant improvements in their AIMS total scores as early as 2 weeks based on an exploratory analysis.16

*Patients may see a response with AUSTEDO as early as 2 weeks (exploratory analysis).

LS, least squares; SE, standard error.

Patients in the AIM-TD study received the AUSTEDO BID formulation.In the ARM-TD study, significant improvement in the AIMS total scores from baseline (P=0.019) was observed at Week 12 with AUSTEDO vs placebo (a 3.0-point reduction vs a 1.6-point reduction).13,15 At the end of titration, patients reached a mean AUSTEDO dosage of 38.8 mg/day (Figure 3.2).14,15

.png) Patients in the ARM-TD study received the AUSTEDO BID formulation.

Patients in the ARM-TD study received the AUSTEDO BID formulation.

In the open-label long-term maintenance study (RIM-TD), improvements were sustained through ~3 years (145 weeks), with a 6.6-point reduction in AIMS score from baseline at Week 145. In addition, a majority of patients and physicians reported symptoms, as measured by the Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) and Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGIC) scales, to be “much improved” or “very much improved” at Week 145. TD symptom improvement was achieved while psychiatric scale scores generally remained stable (Figure 3.3).14,17,18

Over time, an increasing percentage of patients achieved AIMS score improvement17

| • | 56% of patients achieved ≥50% reduction in total AIMS score at Week 80 |

| • | 67% of patients achieved ≥50% reduction in total AIMS score at Week 145 |

.png)

In RIM-TD, the mean dosage of AUSTEDO was 27.5 mg/day at Week 4, 35.7 mg/day at Week 6, and 39.4 mg/day at Week 145.14,17 The mean overall adherence rate (based on pill counts) was approximately 90% over 3 years.14

Patients in the RIM-TD study received the AUSTEDO BID formulation.AUSTEDO has a demonstrated safety and tolerability profile (Table 3.1).13,14

.png)

Adverse reactions with AUSTEDO XR are expected to be similar to AUSTEDO.

Discontinuation due to adverse events (AEs) occurred in 4% of patients taking AUSTEDO versus 3% of patients taking placebo.15,16 Dose reduction due to AEs was required in 4% of patients taking AUSTEDO versus 2% of patients taking placebo.13,16

The most common AEs in patients treated with AUSTEDO (3% and greater than placebo) in controlled studies in patients with TD were nasopharyngitis and insomnia.13

Since patients with TD may be taking a variety of medications, metabolic pathways should be considered when choosing a treatment for TD.13

AUSTEDO XR is the only VMAT2 inhibitor indicated for TD that has no dose restrictions for—or recommendations against—use in patients taking strong CYP3A4/5 inhibitors or inducers.13,19

TD is a movement disorder that can have a profound impact on patients' lives.1 Screening and assessment of TD are important to ensure healthcare providers do not miss the adverse impact it can have on patients' lives. Unfortunately, TD is underrecognized and undertreated, and many patients are still suffering.1,2,5

APA Guidelines recommend VMAT2 inhibitors as first-line treatment for TD that has an impact on the patient, regardless of severity.9 Therefore, once a diagnosis has been made, treatment of TD should be considered.9,20

AUSTEDO was shown in 2 pivotal trials to result in rapid and significant symptom control as measured by changes in patients' AIMS scores, and comparable results were observed in a long-term study of ~3 years.14-16

Patients receiving AUSTEDO may see a response as early as 2 weeks (exploratory analysis).16 In the clinical trial AIM-TD, 71% of patients taking AUSTEDO 36 mg/day saw reductions in their uncontrolled movements.14,16 Over time in the open-label extension study RIM-TD, an increasing percentage of patients achieved AIMS score improvement.17

AUSTEDO has a demonstrated safety and tolerability profile,13,14 and the most common AEs for AUSTEDO in controlled studies in patients with TD were nasopharyngitis and insomnia.13

1. Caroff SN, Campbell EC, Carroll B. Pharmacological treatment of tardive dyskinesia: recent developments. Expert Rev Neurother. 2017;17(9):871-881. 2. Hauser RA, Meyer JM, Factor SA, et al. Differentiating tardive dyskinesia: a video-based review of antipsychotic-induced movement disorders in clinical practice. CNS Spectr. 2022;27(2):208-217. 3. Hirschfeld RM, Bowden CL, Gitlin MJ, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder, second edition. Accessed May 15, 2022. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/bipolar.pdf 4. Gelenberg AJ, Freeman MP, Markowitz JC, et al; Work Group on Major Depressive Disorder. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder, third edition. 2010. Accessed June 3, 2022. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf 5. Caroff SN, Citrome L, Meyer J, et al. A modified Delphi consensus study of the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of tardive dyskinesia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(2):19cs12983. 6. Cutler AJ, Caroff SN, Tanner CM, et al. Presence and impact of possible tardive dyskinesia in patients prescribed antipsychotics: results from the RE-KINECT study. CNS Spectr. 2019;24(1):176-177. 7. Caroff SN, Yeomans K, Lenderking, WR, et al. RE-KINECT: a prospective study of the presence and healthcare burden of tardive dyskinesia in clinical practice settings. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;40(3):259-268. 8. Citrome L. Personal communication. September 30, 2021. 9. American Psychiatric Association. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2021. Accessed May 25, 2022. https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/appi.books.9780890424841 10. Jain R. Can the AIMS exam be conducted via telepsychiatry? Psych Congress Network. December 9, 2019. Accessed May 20, 2022. https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/pcn/article/can-aims-exam-be-conducted-telepsychiatry 11. Jain R. Personal communication. July 19, 2020. 12. Jackson R. Personal communication. July 19, 2020. 13. AUSTEDO® XR (deutetrabenazine) extended-release tablets/AUSTEDO® current Prescribing Information. Parsippany, NJ: Teva Neuroscience, Inc. 14. Data on file. Parsippany, NJ: Teva Neuroscience, Inc. 15. Fernandez HH, Factor SA, Hauser RA, et al. Randomized controlled trial of deutetrabenazine for tardive dyskinesia: the ARM-TD study. Neurology. 2017;88(21):2003-2010. 16. Anderson KE, Stamler D, Davis MD, et al. Deutetrabenazine for treatment of involuntary movements in patients with tardive dyskinesia (AIM-TD): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(8):595-604. 17. Hauser RA, Barkay H, Fernandez HH, et al. Long-term deutetrabenazine treatment for tardive dyskinesia is associated with sustained benefits and safety: a 3-year, open-label extension study. Front Neurol. 2022;23:773999. 18. Hauser RA, Barkay H, Fernandez HH, et al. Long-term deutetrabenazine treatment for tardive dyskinesia is associated with sustained benefits and safety: a 3-year, open-label extension study [supplementary materials]. Front Neurol. 2022;23:773999. 19. Ingrezza® (valbenazine) capsules. Prescribing Information. San Diego, CA: Neurocrine Biosciences, Inc. 20. Keepers GA, Fochtmann LJ, Anzia JM, et al. The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(9):868-872.

IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION

Indications and Usage

AUSTEDO® XR (deutetrabenazine) extended-release tablets and AUSTEDO® (deutetrabenazine) tablets are indicated in adults for the treatment of chorea associated with Huntington's disease and for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia.

Important Safety Information

Depression and Suicidality in Patients with Huntington's Disease: AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO can increase the risk of depression and suicidal thoughts and behavior (suicidality) in patients with Huntington's disease. Balance the risks of depression and suicidality with the clinical need for treatment of chorea. Closely monitor patients for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidality, or unusual changes in behavior. Inform patients, their caregivers, and families of the risk of depression and suicidality and instruct them to report behaviors of concern promptly to the treating physician. Exercise caution when treating patients with a history of depression or prior suicide attempts or ideation. AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO are contraindicated in patients who are suicidal, and in patients with untreated or inadequately treated depression.

Contraindications: AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO are contraindicated in patients with Huntington's disease who are suicidal, or have untreated or inadequately treated depression. AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO are also contraindicated in: patients with hepatic impairment; patients taking reserpine or within 20 days of discontinuing reserpine; patients taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), or within 14 days of discontinuing MAOI therapy; and patients taking tetrabenazine or valbenazine.

Clinical Worsening and Adverse Events in Patients with Huntington's Disease: AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO may cause a worsening in mood, cognition, rigidity, and functional capacity. Prescribers should periodically re-evaluate the need for AUSTEDO XR or AUSTEDO in their patients by assessing the effect on chorea and possible adverse effects.

QTc Prolongation: AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO may prolong the QT interval, but the degree of QT prolongation is not clinically significant when AUSTEDO XR or AUSTEDO is administered within the recommended dosage range. AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO should be avoided in patients with congenital long QT syndrome and in patients with a history of cardiac arrhythmias.

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS), a potentially fatal symptom complex reported in association with drugs that reduce dopaminergic transmission, has been observed in patients receiving tetrabenazine. The risk may be increased by concomitant use of dopamine antagonists or antipsychotics. The management of NMS should include immediate discontinuation of AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO; intensive symptomatic treatment and medical monitoring; and treatment of any concomitant serious medical problems.

Akathisia, Agitation, and Restlessness: AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO may increase the risk of akathisia, agitation, and restlessness. The risk of akathisia may be increased by concomitant use of dopamine antagonists or antipsychotics. If a patient develops akathisia, the AUSTEDO XR or AUSTEDO dose should be reduced; some patients may require discontinuation of therapy.

Parkinsonism: AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO may cause parkinsonism in patients with Huntington's disease or tardive dyskinesia. Parkinsonism has also been observed with other VMAT2 inhibitors. The risk of parkinsonism may be increased by concomitant use of dopamine antagonists or antipsychotics. If a patient develops parkinsonism, the AUSTEDO XR or AUSTEDO dose should be reduced; some patients may require discontinuation of therapy.

Sedation and Somnolence: Sedation is a common dose-limiting adverse reaction of AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO. Patients should not perform activities requiring mental alertness, such as operating a motor vehicle or hazardous machinery, until they are on a maintenance dose of AUSTEDO XR or AUSTEDO and know how the drug affects them. Concomitant use of alcohol or other sedating drugs may have additive effects and worsen sedation and somnolence.

Hyperprolactinemia: Tetrabenazine elevates serum prolactin concentrations in humans. If there is a clinical suspicion of symptomatic hyperprolactinemia, appropriate laboratory testing should be done and consideration should be given to discontinuation of AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO.

Binding to Melanin-Containing Tissues: Deutetrabenazine or its metabolites bind to melanin-containing tissues and could accumulate in these tissues over time. Prescribers should be aware of the possibility of long-term ophthalmologic effects.

Common Adverse Reactions: The most common adverse reactions for AUSTEDO (>8% and greater than placebo) in a controlled clinical study in patients with Huntington's disease were somnolence, diarrhea, dry mouth, and fatigue. The most common adverse reactions for AUSTEDO (4% and greater than placebo) in controlled clinical studies in patients with tardive dyskinesia were nasopharyngitis and insomnia. Adverse reactions with AUSTEDO XR extended-release tablets are expected to be similar to AUSTEDO tablets.

Please see accompanying full Prescribing Information, including Boxed Warning.

Medina, Ohio

This interview with a prominent thought leader on TD examines screening and assessment of this disorder and how it can be done virtually.

Q:When speaking about tardive dyskinesia (TD), we often hear the term “assessment” used with “screening.” How is TD screening different from TD assessment?

A: Since TD can have a profound impact on patients' lives, we need to identify it if it's there. We screen for TD to determine if the patient has abnormal movements that would lead to a diagnosis of TD or a different movement disorder. If we make a diagnosis of TD, we assess the severity and impact of TD using a structured examination.

Screening for TD involves looking for abnormal movements, observing the patients' actions, asking them questions, listening to their responses, and speaking to the people around them about what they may have noticed.

During screening, providers may choose to use an activation maneuver to help them better evaluate the movements and confirm the diagnosis. Providers may even choose to use a structured assessment during screening if it will provide them with more confidence in making a diagnosis.

Assessment generally takes place after a diagnosis is made. We assess for TD to determine the severity and the impact of the disorder by doing examinations.

Q:Based on what you see in your practice and the impact TD has on your patients, how critical would you say it is to screen for TD?

A: TD is a devastating condition, not only physically but also psychosocially, and the effect extends to the patients' family members and caregivers.

Screening is critical for several reasons. The first reason we must screen for TD is clinical. Screening involves looking for abnormal movements that can help us make a diagnosis. We screen because we know that TD impacts patients' lives and can hinder our ability to manage the underlying mental health disorder. If we don't screen, we miss the opportunity to help the patient as well as our practice.

The second reason is a medical-legal one. In the past, there was no treatment for TD. However, now if you don't screen, you're not practicing the standard of care to address an issue that may have been caused by prescribing an antipsychotic drug (APD). Because we now have treatments for TD, the risk-reward of using an APD is lower, but you still have to look for movements and treat them if they occur. The availability of vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors has done more than just provide a treatment for TD, because the opportunity to prescribe APDs for mental health disorders provides more options for the patient.

It's important to keep in mind when screening for TD that we can't just go by what patients complain about. Having TD and complaining about TD are two different things. Patients with schizophrenia, for example, are less likely to talk or complain about abnormal movements; however, this does not mean these movements don't impact them or their families.

Q: So the assessment process follows screening. What are the key features of assessment?

A:To assess, clinicians use a formal, structured examination that measures the severity of the movements and the impact on the patient. The structured assessment used is typically the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale, or AIMS. Given the paucity of available validated tools, a formal assessment using the AIMS is essential.

The impact of TD is of primary importance because even those with mild TD severity may be impacted considerably. When assessing for TD, remember that we want to document not only symptom severity but also impact. Specifically, AIMS item 9 looks at "incapacitation due to movements,” which provides an entry to considering the impact TD has on patients and their families.

Q: Another important consideration is frequency. How often should healthcare providers (HCPs) screen for and assess TD? Should they do it every time they encounter the patient?

A:Absolutely—at every visit. At our clinic, we screen for TD every time we see a patient who has been prescribed APDs, and we assess patients diagnosed with TD at every visit.

One reason we screen and assess at every visit is because symptoms may have emerged or become more severe since we last examined the patient, and consequently the impact may have become more severe.

Another reason is that some patients can mask their symptoms for a short period of time. They may be embarrassed and cover up their TD by making their abnormal movements look intentional.

It's therefore essential to have a very high index of suspicion and to remember that, because TD can affect any muscle group, it may not initially look the way we imagine TD to present in a patient. If, for instance, you notice symptoms such as difficulty swallowing or trouble breathing, then during screening you should be asking the patient questions about these potential symptoms.

Q:Given that some patients try to mask their TD symptoms, how do you approach patients in cases in which you think they may be hiding abnormal movements?

A: Let me provide a couple of examples. I saw a patient for the first time. He had a brush with him, and he was brushing his body in front of me. It seemed very strange, but it turned out that he had TD and brushing his body allowed his movements to look intentional.

I had a female patient who had an undulating movement with her neck and she kept leaning into me. At first, it seemed inappropriate until I realized she was trying to make her abnormal neck movements into a purposeful movement.

These patients have an awareness of their movements and they try to hide them. In these instances, I might try using activation maneuvers because it takes control away from the patients so that the abnormal movements may emerge.

I want my patients to feel comfortable, so I let them know that I understand how this may be embarrassing for them. I try to emphasize that TD is not their fault and that TD does not diminish them as a person. Of course, I also let them know that treatment is available.

Q:Traditionally, screening and assessment are conducted in the office, but it's become critical to be able to perform these tests in the virtual setting. How do screenings differ in an office setting versus in a virtual setting?

A: In any setting, you have to have a high index of suspicion for TD. But we need an even higher index of suspicion in the virtual setting because we are more likely to miss it there. So we do our due diligence in the virtual setting, whether we're seeing patients via video or we're simply speaking to them over the phone. With virtual visits, if you don't screen and assess for abnormal movements every time, there is more of a chance you'll miss diagnosing TD.

During a virtual visit, it may help you if you ask the patient to change camera angles. If they cannot do it, ask if there is anyone with them who can help, whether a family member or a case manager.

Many patients, particularly those with schizophrenia, do not have smart phones with video capability. Over the regular telephone that only uses voice, you can pay attention to the way they talk. If there are abnormal tongue movements, you may hear a type of lisp as they speak, and it is also possible to hear lip smacking over the phone. Additionally, you can listen for labored breathing, which can be a sign of pronounced TD.

We need to train ourselves to pay attention to any change in their voice. You can also ask to speak to a family member or support staff about any abnormal movements they may have witnessed.

Q:For patients without a smart phone, if you suspect abnormal movements during your phone call, what is the next step?

A: If I suspect TD, I need to talk to someone—whether it's support staff or a family member—who sees the patient every day (or at least several days a week for a full day). Next, it is important to get collateral information on APD side effects such as TD. When TD is diagnosed, it should be treated.

Q:So screening can be performed effectively during the virtual visit. What about assessment? For example, can the AIMS be performed effectively in the virtual setting?

A: The AIMS can absolutely be performed effectively in a virtual setting if it is a video-to-video visit. Once you have properly performed 10 or 15 AIMS, you are not going to miss TD, even in the virtual setting. And if you are well trained, you will be able to differentiate TD from parkinsonism in the virtual setting.

I think being able to make a virtual diagnosis will vary among providers based on their level of expertise in diagnosing TD. In general, psychiatrists have received training, but many generalists have not had the opportunity to be trained in use of the AIMS. Certainly, providers need to gain comfort with diagnosing TD in general, including diagnosing virtually. I believe it is our obligation to ensure we are well trained and well equipped to recognize TD and then treat it.

Q:Do you have any tips for performing screenings and the AIMS assessment virtually?

A:We use the hierarchy of probability to start with the face. If I do not see any abnormal movements there, then at that point I would ask the patient to show me their legs and to take off their socks. If you have a good rapport with your patients, they will do it. It really hinges on what kind of relationship you have. If you have not had the opportunity to develop a good rapport with your patients, whether the visit is virtual or real, you will miss something because they are not going to tell you everything.

When the feet are resting on the ground, some movements can be masked. If possible, have the patient sit on a tall chair or bed so that their feet are dangling above the floor.

Having a good camera angle is extremely important. If you have a comfortable relationship with your patient, I have found that you can walk them or their care partner through setting it up.

Q:The American Psychiatric Association (APA) recommends that if TD symptoms have an impact, treatment should be considered regardless of severity. How do you go about determining the impact of TD, especially in the virtual environment?

A:Once you have diagnosed the patient, you need to ask them questions very gently. Low-functioning patients with schizophrenia, for example, do not want to talk about their TD. Using straightforward language, you can say, “I noticed that you have some movements of your lips. How is that affecting your day-to-day functioning? Is it stopping you from leaving your room or going outside?” Even if the patient says nothing about impact, the impact may be there. If most people would be embarrassed or troubled by the movement, then the impact clearly exists.

Once you have screened for TD, made a diagnosis, and assessed its severity and impact, the next step is to make a clinical decision on how you want to treat the patient's TD. In my mind, if TD is clinically diagnosable, I am going to treat it. If I can make even a small difference in that patient's life, I am going to go ahead and do it.

Historically, clinicians used the term “extrapyramidal symptoms” (EPS) as a catchphrase to describe the abnormal movements they observed and would prescribe benztropine regardless of what the movements looked like. It is essential that every movement disorder be treated with an appropriate medication to ensure that the disorder is not inadvertently exacerbated.

It's important to add that if you diagnose a patient with TD during a virtual video visit, you can start treatment right away. You do not need them to come into the office first—it can all be done virtually.

Once patients have been diagnosed with TD and started treatment, we need to continue to assess its severity at every visit to see if it is progressing or diminishing. And we need to let every one of our patients know that we are going to do the best we can by them.

Caroff SN. Overcoming barriers to effective management of tardive dyskinesia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:785-794. Caroff SN, Citrome L, Meyer J, et al. A modified Delphi consensus study of the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of tardive dyskinesia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(2):19cs12983. Citrome L. Treating TD in the COVID-19 era: 5 steps to success. Psychiatry & Behavioral Health Learning Network. June 8, 2020. Accessed September 28, 2021. https://www.psychcongress.com/multimedia/treating-td-covid-19-era-5-steps-success Hauser RA, Meyer JM, Factor SA, et al. Differentiating tardive dyskinesia: a video-based review of antipsychotic-induced movement disorders in clinical practice. CNS Spectr. 2022;27(2):208-217. Jackson R, Brams MN, Citrome L, et al. Assessment of the impact of tardive dyskinesia in clinical practice: consensus panel recommendations. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:1589-1597. Jain R. Can the AIMS exam be conducted via telepsychiatry? Psych Congress Network. December 9, 2019. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/pcn/article/can-aims-exam-be-conducted-telepsychiatry McEvoy J, Park T, Schilling T, Terasawa E, Ayyagari R, Carroll B. The burden of tardive dyskinesia secondary to antipsychotic medication use among patients with mental disorders. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(7):1205-1214. Srinivasan R, Ben-Pazi H, Dekker M, et al. Telemedicine for hyperkinetic movement disorders. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y). 2020;10. doi:10.7916/tohm.v0.698 Ward KM, Citrome L. Antipsychotic-related movement disorders: drug-induced parkinsonism vs. tardive dyskinesia—key differences in pathophysiology and clinical management. Neurol Ther. 2018;7(2):233-248.