One clinical concern in psychiatry is drug-induced movement disorders caused by antipsychotic drugs (APDs).4-6 Historically, the drug-induced movement disorders known as tardive dyskinesia (TD) and drug-induced parkinsonism (DIP) were both referred to as “extrapyramidal symptoms” (EPS).7 However, TD and DIP are 2 distinct conditions with different treatment approaches.1-3

These 2 conditions both result from dopamine receptor-blocking drugs3,8; however, the conditions occur through different mechanisms caused by the dopamine blockade.8 DIP is thought to occur when acute dopamine receptor blockade leads to reduced dopamine signaling8; TD is thought to occur when chronic dopamine receptor blockade causes an upregulation of dopamine receptors that subsequently results in increased dopamine signaling.8

Regardless of severity, both TD and DIP can have a significant impact on patients' lives, and therefore, treatment is important.9,10 However, since the distinct treatments for TD and DIP are specific to each disorder, and treatment for one can worsen the other, it is critical to differentiate between the two.1-3

Key features that differentiate TD and DIP include timing of onset and the nature and frequency of movements.8,11-13 “Tardive” means “delayed” or “late”; most people take an APD for months or years before developing TD.14 In contrast, the onset of DIP tends to be acute; it usually occurs within days or weeks after the administration of APDs or an increase in the APD dose.8

“Dyskinesia” refers to involuntary muscle movements15; TD is characterized by an excess of movements that are irregular, jerky, and unpredictable.13,16 Abnormal movements from TD are accompanied by normal muscular tone (Figure 1.1).12

Parkinsonism is characterized by a paucity of movement. When movements occur, they are typically rhythmic and may be accompanied by rigidity. These motor symptoms may appear symmetrically in patients with DIP, whereas symptoms in patients with Parkinson's disease may first present with asymmetry.10,12,17,18

Movements are irregular, unpredictable, jerky, and twitchy

Movements are rhythmic

Movements are excessive and continuous

Paucity of movements

Movements accompanied by normal muscular tone

Movements may be accompanied by rigidity

Differentiating DIP from TD can be readily done, provided that the clinician is aware of the differences in symptoms and the timing of symptom onset.8,11

Clinicians can identify abnormal movements through observation and inquiry into the patient's awareness of their movements.19 The American Psychiatric Association (APA) recommends screening for abnormal movements at every health visit either by clinical observation or through the use of a structured instrument such as the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) examination.4 Their recommendations include performing a formal AIMS exam once or twice a year in patients taking APDs, depending on the patient's risk factors.4

The AIMS is a 12-item scale in which items 1 through 7 assess the severity of the involuntary movements of TD across body regions and items 8 through 12 address global severity, patient awareness and distress, and dental issues that may impact the ability to identify abnormal movements.20

At times during the AIMS exam, the identification of movements outside the realm of TD may emerge. For example, during an AIMS exam, the clinician may observe a tremor when the patient is at rest or with the arms outstretched.21 Slowness or a shuffling gait may be detected when the patient is walking.21 Rigidity may be suspected if the patient exhibits a lack of arm swing when walking or acknowledges experiencing stiffness.7,21,22 The presentation of these symptoms may lead to a diagnosis of DIP.18,20,23

When symptoms of TD and DIP present simultaneously, each disorder should be treated appropriately and independently.1-3,24 If needed, the patient can be referred to a movement disorder specialist for further evaluation and treatment.

It is important to take into consideration that if parkinsonism develops after the patient has been on an APD for a lengthy period of time, and it doesn’t resolve with the reduction of the APD, then the patient may have Parkinson's disease and need a referral to a neurologist for further evaluation.10

Distinguishing between TD and DIP is critical because the treatment approaches are different, and treatment for one disorder may worsen the other.1-3 As stated in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR), “It is imperative to distinguish medication-induced parkinsonism from tardive dyskinesia because...anticholinergic medications may worsen...tardive dyskinesia.”16 The DSM-5-TR goes on to say that “the symptoms of tardive dyskinesia tend to be worsened by...anticholinergic medications (such as benztropine, commonly used to manage medication-induced parkinsonism).”16

When anticholinergic therapy is required for patients with DIP, consideration must be given to the duration of therapy.4 Anticholinergics should not be prescribed without taking into account their acute and, even more pertinently, their chronic use.4 According to the APA treatment guidelines, “if an anticholinergic medication is used, it is important to adjust the medication to the lowest dose that is able to treat the parkinsonian symptoms. In addition, it is also important to use the medication for the shortest time necessary.”4 The APA guidelines also state that “medications with anticholinergic effects can result in multiple difficulties for patients, including impaired quality of life, impaired cognition, and significant health complications.”4 Long-term use of these agents, particularly in the elderly, increases the risk of cognitive decline.26

Because it is recommended to use anticholinergics for the shortest time necessary, another approach for DIP is to use an alternative antipsychotic with less dopamine D2 binding affinity.4 That, in turn, will improve the DIP, and the patient can slowly be weaned off the anticholinergic.4

Despite this guidance, anticholinergics such as benztropine continue to be used prophylactically and chronically in patients with DIP, and sometimes to treat TD.7,25 Historically, all drug-induced movement disorders were categorized under the term “EPS” because the differences between them were not necessarily understood. Additionally, vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors were not available, so there was no reason for clinicians to alter their approach to treatment.7,25

Although anticholinergics are used as treatments for DIP, they should be avoided in patients with TD because they can exacerbate dyskinetic symptoms.1,8,27,28 Conversely, treatment with a VMAT2 inhibitor can result in DIP in some patients or worsen existing DIP.29

It is understood that a drug-induced movement disorder can impact the course of a patient's underlying mental health disorder.13,30-33 A VMAT2 inhibitor is recommended as a first-line treatment for TD, regardless of symptom severity, if the movements are having an impact on the patient.8

Although TD and DIP are both the result of treatment with dopamine receptor-blocking agents, including APDs, they are distinct disorders.4,5,8 It is critical for clinicians to differentiate between them, primarily because the treatment strategy for one may exacerbate the other.1-3 Furthermore, a drug-induced movement disorder can impact the course of a patient's underlying mental health disorder.13,30-32 Therefore, a proper diagnosis and subsequent treatment are critical to ensuring that patients being treated for their psychiatric condition are not destabilized for lack of appropriate treatment of their movement disorder.13,30-33

References

Some drugs can cause neurological adverse effects, including movement disorders. Tardive dyskinesia (TD) and drug-induced parkinsonism (DIP), movement disorders caused by treatment with antipsychotic drugs (APDs), are often conflated. However, not only are TD and DIP distinct, but treatment for one may worsen the other. Correctly identifying symptoms of TD versus DIP and accurately diagnosing each disorder are critical to facilitating the appropriate treatment selection.

Let's consider a specific patient's journey through differential diagnosis and treatment.

Joe was diagnosed with schizophrenia at age 24. At that time, his psychiatrist prescribed a long-acting, injectable, typical APD.

Within several weeks of Joe’s initial treatment for schizophrenia, Joe presented with rigidity in his arms and legs.

Just a few weeks after being diagnosed with schizophrenia and prescribed an APD, Joe’s experience with rigidity in his limbs led to a diagnosis of DIP. At that point, Joe’s psychiatrist prescribed benztropine, 1 mg twice daily, an anticholinergic for DIP. Joe continued on these treatments at the originally prescribed doses for close to 3 decades.

Until a number of months ago, Joe had not exhibited any symptoms of DIP. However, several months ago, Joe visited his community mental health center for a regularly scheduled appointment. His case manager noticed that Joe was having some difficulty walking, a symptom that had never been detected previously. Instead of lifting his feet, Joe presented with more of a shuffling gait.

The case worker made an appointment for Joe with his psychiatrist, who recognized the shuffling to be a breakthrough symptom of DIP. Joe’s psychiatrist increased his dosage of benztropine from 1 mg twice daily to 2 mg twice daily over the span of 1 month.

During 2 subsequent appointments over 2 months, Joe’s psychiatrist noted a slight improvement in Joe’s gait. However, at the second follow-up, the psychiatrist observed that Joe’s fingers were twitching in jerky motions. Based on these movements, his psychiatrist increased Joe’s benztropine dosage to 3 mg twice daily over the span of 1 month.

A month later, at Joe’s third follow-up appointment, Joe presented with finger movements that were more exaggerated and frequent than previously, and he also exhibited some facial grimacing. Joe told his psychiatrist that these movements had led him to isolate from others because he felt uncomfortable being around people.

The psychiatrist performed an examination with the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS). While conducting the exam, his psychiatrist observed jerky, rapid movements commensurate with TD together with the rigidity associated with DIP and determined that Joe had both TD and DIP.

The complexity of simultaneously treating TD and DIP led Joe’s psychiatrist to confer with a movement disorder specialist (MDS). Together, they determined that they would first address the DIP symptoms by switching Joe from a long-acting, injectable, typical APD to a long-acting, injectable, atypical APD over the span of 3 months.

At the same time, they would decrease the benztropine dosage from 3 mg twice daily to 2 mg twice daily over the span of 1 month, down to 1 mg twice daily over a second month, and to discontinuation over a third month. After 3 months, they would reassess Joe. If his schizophrenia symptoms were stable and his DIP symptoms had improved, they would continue with the atypical APD.

Following the switch to the atypical APD over 3 months, Joe’s schizophrenia symptoms remained stable and his shuffling gait improved. Since the benztropine reduction from 3 mg to discontinuation over 3 months did not lead to any DIP symptoms, Joe no longer required medication for DIP. However, his TD symptoms—the finger movements and facial grimacing—were still occurring and causing him to isolate himself.

Joe’s physicians decided to initiate treatment for his TD with a vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitor. Following the start of treatment with the VMAT2 inhibitor, Joe had a reduction in both his finger movements and facial grimacing.

Joe’s psychiatrist and MDS had to treat not only Joe’s schizophrenia but his DIP and TD as well. Although his typical APD kept Joe’s schizophrenia symptoms stable, they wanted to see if it was causing his DIP. If switching APDs reduced his DIP while keeping his schizophrenia symptoms stable, it would mean that his original APD caused DIP.

The latest American Psychiatric Association (APA) guideline recommendations state that anticholinergics such as benztropine should be used for the shortest time and at the lowest dose possible, so Joe’s decades-long treatment with benztropine did not line up with APA guidelines.

In a patient with comorbid TD and DIP, since benztropine can make TD worse, it can be helpful to wean the patient off benztropine treatment for DIP before reassessing and tackling the TD. For Joe, once his benztropine had been discontinued, because his new APD was not causing DIP, he no longer required DIP treatment. However, he still presented with TD, so a TD treatment was indicated.

According to APA guidelines, if TD symptoms are impacting the patient, treatment with a VMAT2 inhibitor is recommended.

In this challenging case example, Joe had both DIP and TD in addition to schizophrenia, and at first, his TD symptoms were mistaken for DIP. As a result, the benztropine dose was increased, and Joe’s TD symptoms worsened. Replacing the typical APD with an atypical APD, discontinuing benztropine, and prescribing a VMAT2 inhibitor proved to be the appropriate treatment for Joe. Understanding how to differentiate TD from DIP and the appropriate treatment for each can help you manage patients with these 2 drug-induced movement disorders.

Bergman H, Rathbone J, Agarwal V, Soares-Weiser K. Antipsychotic reduction and/or cessation and antipsychotics as specific treatments for tardive dyskinesia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2(2):CD000459.

Chouksey A, Pandey S. Clinical spectrum of drug-induced movement disorders: a study of 97 patients. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y). 2020;10:48.

Mentzel CL, Bakker PR, van Os J, et al. Effect of antipsychotic type and dose changes on tardive dyskinesia and parkinsonism severity in patients with a serious mental illness: The Curaçao Extrapyramidal Syndromes Study XII. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(3):e279-e285.

Patterson-Lomba O, Ayyagari R, Carroll B. Risk assessment and prediction of TD incidence in psychiatric patients taking concomitant antipsychotics: a retrospective data analysis. BMC Neurol. 2019;19(1):174.

Rekhi G, Tay J, Lee J. Impact of drug-induced parkinsonism and tardive dyskinesia on health-related quality of life in schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol. 2022;36(2):183-190.

Savitt D, Jankovic J. Tardive syndromes. J Neurol Sci. 2018;389:35-42.

Sykes DA, Moore H, Stott L, et al. Extrapyramidal side effects of antipsychotics are linked to their association kinetics at dopamine D2 receptors. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):763.

Tardive dyskinesia (TD), a disorder characterized by abnormal, involuntary movements,3,4 is the result of exposure to antipsychotic drugs (APDs)2,5,6 prescribed to some patients experiencing mental health disorders.5-7 Historically, drug-induced movement disorders were categorized as “extrapyramidal symptoms” (EPS),8 but in fact, these disorders have distinct pathophysiologies that require different treatments.1,9

TD is thought to occur from the chronic blockade of dopamine receptors by dopamine receptor–blocking agents, such as APDs, resulting in dopamine receptor upregulation and increased dopamine signaling.1 This dopamine receptor upregulation can result in an exaggerated response to dopamine in the form of involuntary movements.10

The FDA approval of vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors for the treatment of TD has been a game-changer for patients and providers. VMAT2 inhibitors are therapeutic agents that cause a depletion of dopamine in presynaptic nerve terminals.12

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) recommends treatment with a VMAT2 inhibitor for patients with TD who experience an impact.2 AUSTEDO XR is a VMAT2 inhibitor indicated for the treatment of TD in adults.11

Deutetrabenazine binds to VMAT2 on the vesicle in the presynaptic neuron.13 The process of reducing dopamine levels in the presynaptic neuron results in less dopamine signaling to the postsynaptic neuron.11,12 Limiting dopamine signaling with the VMAT2 inhibitor deutetrabenazine is believed to lead to fewer abnormal involuntary movements; however, the precise mechanism by which deutetrabenazine exerts its effects on abnormal involuntary movements is unknown.11,12

The efficacy and safety of AUSTEDO were studied in 2 placebo-controlled pivotal trials, Addressing Involuntary Movements in Tardive Dyskinesia (AIM-TD) and Aim to Reduce Movements in Tardive Dyskinesia (ARM-TD), and in a long-term, open-label extension trial.11,14-16

The AIM-TD clinical study was a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose trial (N=222).11,15 Results demonstrated that AUSTEDO significantly reduced the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) total score by 3.3 points from baseline in the 36-mg/day arm (n=55) versus a reduction of 1.4 points with placebo (n=58) at Week 12 (P=0.001).11,15

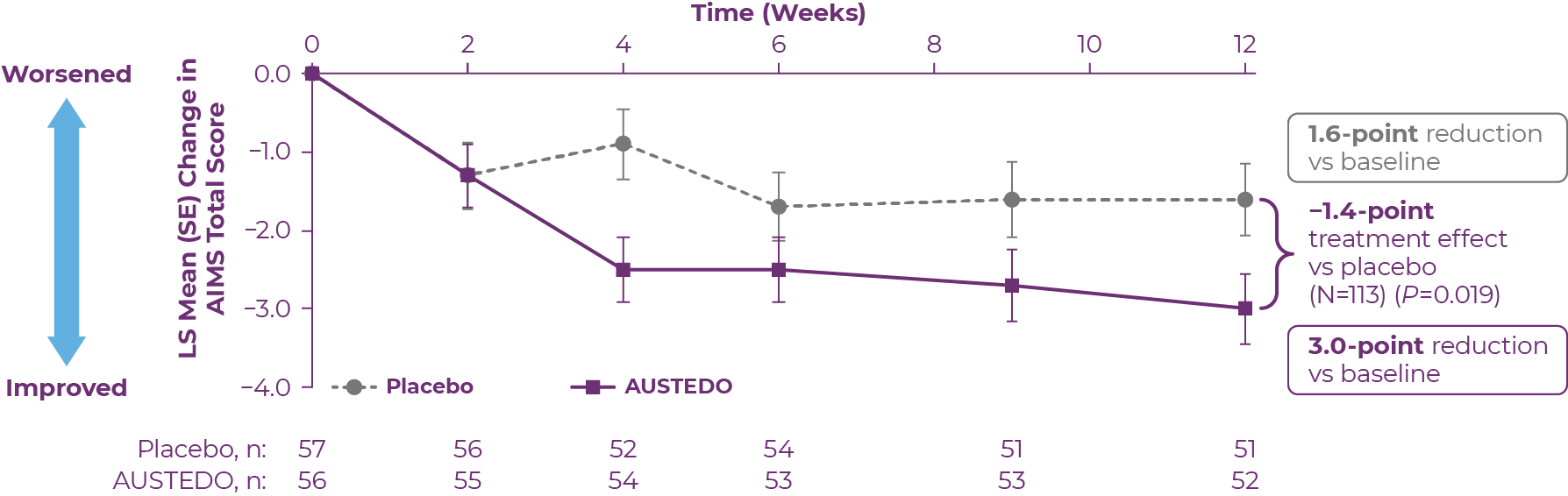

The ARM-TD clinical study was a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, flexible-dose trial.14 In this study, AUSTEDO significantly reduced AIMS total score by 3.0 points from baseline (n=56) versus a reduction of 1.6 points with placebo (n=57) at Week 12 (P=0.019).11,14 At the end of titration, the mean dosage of AUSTEDO was 38.8 mg/day (Figure 3.1).14,16

LS, least squares; SE, standard error.

LS, least squares; SE, standard error.

Patients in the ARM-TD study received the AUSTEDO BID formulation.

The Reducing Involuntary Movements in Participants With Tardive Dyskinesia (RIM-TD) clinical study was a long-term, open-label extension trial. Patients in this study (N=343) had completed AIM-TD or ARM-TD and opted to roll over to RIM-TD following a 1-week washout period.16-18

Patients started on a dosage of AUSTEDO of 12 mg/day, and the dosage was titrated by 6 mg/day weekly to reach a dosage that adequately controlled TD and, at the same time, was tolerated by the patient.18 Symptom control was defined as the change in total AIMS score observed as early as Week 2 during the placebo-controlled clinical trials.16 Sustained results were observed through ~3 years in the open-label extension trial.16-18 At Week 145, the mean AIMS total score was reduced by 6.6 points from baseline.16-18

In the RIM-TD trial, the mean dosage of AUSTEDO was 35.7 mg/day at Week 6 and 39.4 mg/day at Week 145 (Figure 3.2).8,16 At Week 145, a majority of patients and physicians reported symptoms as “much improved” or “very much improved.”18 At 3 years, the mean overall adherence rate (based on pill count) was ~90%.16 TD symptom improvement was achieved while psychiatric scale scores generally remained stable.18,19

.png) Patients in the RIM-TD study received the AUSTEDO BID formulation.

Patients in the RIM-TD study received the AUSTEDO BID formulation.

AUSTEDO has a demonstrated safety and tolerability profile (Table 3.1).

.png)

Adverse reactions with AUSTEDO XR are expected to be similar to AUSTEDO.

Discontinuation due to adverse events (AEs) occurred in 4% of patients taking AUSTEDO versus 3% of patients taking placebo.14,15 Dose reduction due to AEs was required in 4% of patients taking AUSTEDO versus 2% of patients taking placebo.11

The most common AEs in patients treated with AUSTEDO (≥3% and greater than placebo) in controlled studies in patients with TD were nasopharyngitis and insomnia.11

Since patients with TD may be taking a variety of medications, metabolic pathways should be considered when choosing a treatment for TD.11 AUSTEDO XR is the only VMAT2 inhibitor indicated for TD that has no dose restrictions for—or recommendations against—use in patients taking strong CYP3A4/5 inhibitors or inducers.11,20

AUSTEDO XR is available in 12 mg, 18 mg, 24 mg, 30 mg, 36 mg, 42 mg, and 48 mg extended release tablets, providing flexibility for effective and tolerable symptom control.11 The starting dose for patients with TD is 12 mg/day. Clinicians can increase the dose of AUSTEDO XR by 6 mg/day at weekly intervals for individual patients until desired symptom control is tolerably achieved (Figure 3.3).11

Providers can help get their patients started on AUSTEDO XR with the easy-to-use 4-week Titration Kit available through sample and prescription, which will take patients to a dosage of 30 mg/day in 4 weeks. As long as it is tolerated, AUSTEDO XR can be titrated up to a maximum daily dosage of 48 mg or until the patient's symptoms no longer continue to improve.11 Titrating up to the maximum tolerable symptom improvement (to a maximum of 48 mg/day) can help contribute to the treatment objectives shared by patients and their healthcare providers.11

.png)

TD is thought to occur from the blockade of dopamine receptors by APDs, resulting in dopamine receptor upregulation and increased dopamine signaling.1 The APA recommends VMAT2 inhibitors as first-line treatment for TD that has an impact on the patient.2

AUSTEDO XR is a VMAT2 inhibitor for the treatment of TD in adults.11 Deutetrabenazine is thought to bind to VMAT2 on the vesicle in the presynaptic neuron and inhibit the uptake of dopamine into synaptic vesicles. Limiting dopamine signaling is believed to lead to fewer abnormal involuntary movements, but the precise mechanism of action of deutetrabenazine is unknown.11,12

Rapid and significant symptom control was demonstrated in 2 pivotal trials, with results sustained over ~3 years in the open-label extension study. Symptom control defined as change in total Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) score. Patients may see a response with AUSTEDO in as early as 2 weeks (exploratory analysis).16 Patients in the ARM-TD and AIM-TD studies received the AUSTEDO BID formulation.

AUSTEDO has a demonstrated safety and tolerability profile as well as a distinct metabolic profile.11,16

AUSTEDO XR is a one pill, once-daily treatment option that provides flexibility for effective and tolerable symptom control. The dosing and titration of AUSTEDO XR is an important factor in symptom control.11 For individual patients, AUSTEDO XR should be dosed based on symptom control and tolerability.11 The average daily dosage in clinical trials was >36 mg/day, and AUSTEDO XR can be titrated to a maximum dosage of 48 mg/day.11

1. Ward KM, Citrome L. Antipsychotic-related movement disorders: drug-induced parkinsonism vs. tardive dyskinesia—key differences in pathophysiology and clinical management. Neurol Ther. 2018;7(2):233-248. 2. American Psychiatric Association. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2021. Accessed August 4, 2022. https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/appi.books.9780890424841 3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2022. 4. Caroff SN. Overcoming barriers to effective management of tardive dyskinesia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:785-794. 5. Hirschfeld RM, Bowden CL, Gitlin MJ, et al; Work Group on Bipolar Disorder. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2010. Accessed July 31, 2022. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/bipolar.pdf 6. Gelenberg AJ, Freeman MP, Markowitz JC, et al; Work Group on Major Depressive Disorder. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2010. Accessed July 14, 2022. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf 7. Keepers GA, Fochtmann LJ, Anzia JM, et al. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(9):868-872. 8. Hauser RA, Meyer JM, Factor SA, et al. Differentiating tardive dyskinesia: a video-based review of antipsychotic-induced movement disorders in clinical practice. CNS Spectr. 2022:27(2):208-217. 9. Kucharski LT, Unterwald EM. Symptomatic treatment of tardive dyskinesia: a word of caution. Schizophr Bull. 1981;7(4):571-573. 10. Vasan S, Padhy RK. Tardive dyskinesia. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated April 30, 2022. Accessed August 4, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448207/ 11. AUSTEDO® XR (deutetrabenazine) extended-release tablets/AUSTEDO® current Prescribing Information. Parsippany, NJ: Teva Neuroscience, Inc. 12. Caroff SN, Aggarwal S, Yonan C. Treatment of tardive dyskinesia with tetrabenazine or valbenazine: a systematic review. J Comp Eff Res. 2018;7(2):135-148. 13. National Center for Biotechnology Information Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. Vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors. Updated April 2, 2019. Accessed August 4, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK548187/#:~:text=The%20vesicular%20monoamine%20transporter%20type,neuroleptic%20medications%20(tardive%20dyskinesia) 14. Fernandez HH, Factor SA, Hauser RA, et al. Randomized controlled trial of deutetrabenazine for tardive dyskinesia: the ARM-TD study. Neurology. 2017;88(21):2003-2010. 15. Anderson KE, Stamler D, Davis MD, et al. Deutetrabenazine for treatment of involuntary movements in patients with tardive dyskinesia (AIM-TD): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(8):595-604. 16. Data on file. Parsippany, NJ: Teva Neuroscience, Inc. 17. ClinicalTrials.gov. NCT02198794. Last updated April 1, 2022. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02198794 18. Hauser RA, Barkay H, Fernandez HH, et al. Long-term deutetrabenazine treatment for tardive dyskinesia is associated with sustained benefits and safety: a 3-year, open-label extension study. Front Neurol. 2022;23(13):773999. 19. Hauser RA, Barkay H, Fernandez HH, et al. Long-term deutetrabenazine treatment for tardive dyskinesia is associated with sustained benefits and safety: a 3-year, open-label extension study [supplementary materials]. Front Neurol. 2022;23(13):773999. 20. Ingrezza® (valbenazine) capsules. Prescribing Information. San Diego, CA: Neurocrine Biosciences, Inc.

IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION

Indications and Usage

AUSTEDO® XR (deutetrabenazine) extended-release tablets and AUSTEDO® (deutetrabenazine) tablets are indicated in adults for the treatment of chorea associated with Huntington's disease and for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia.

Important Safety Information

Depression and Suicidality in Patients with Huntington's Disease: AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO can increase the risk of depression and suicidal thoughts and behavior (suicidality) in patients with Huntington's disease. Balance the risks of depression and suicidality with the clinical need for treatment of chorea. Closely monitor patients for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidality, or unusual changes in behavior. Inform patients, their caregivers, and families of the risk of depression and suicidality and instruct them to report behaviors of concern promptly to the treating physician. Exercise caution when treating patients with a history of depression or prior suicide attempts or ideation. AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO are contraindicated in patients who are suicidal, and in patients with untreated or inadequately treated depression.

Contraindications: AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO are contraindicated in patients with Huntington’s disease who are suicidal, or have untreated or inadequately treated depression. AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO are also contraindicated in: patients with hepatic impairment; patients taking reserpine or within 20 days of discontinuing reserpine; patients taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), or within 14 days of discontinuing MAOI therapy; and patients taking tetrabenazine or valbenazine.

Clinical Worsening and Adverse Events in Patients with Huntington's Disease: AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO may cause a worsening in mood, cognition, rigidity, and functional capacity. Prescribers should periodically re-evaluate the need for AUSTEDO XR or AUSTEDO in their patients by assessing the effect on chorea and possible adverse effects.

QTc Prolongation: AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO may prolong the QT interval, but the degree of QT prolongation is not clinically significant when AUSTEDO XR or AUSTEDO is administered within the recommended dosage range. AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO should be avoided in patients with congenital long QT syndrome and in patients with a history of cardiac arrhythmias.

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS), a potentially fatal symptom complex reported in association with drugs that reduce dopaminergic transmission, has been observed in patients receiving tetrabenazine. The risk may be increased by concomitant use of dopamine antagonists or antipsychotics. The management of NMS should include immediate discontinuation of AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO; intensive symptomatic treatment and medical monitoring; and treatment of any concomitant serious medical problems.

Akathisia, Agitation, and Restlessness: AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO may increase the risk of akathisia, agitation, and restlessness. The risk of akathisia may be increased by concomitant use of dopamine antagonists or antipsychotics. If a patient develops akathisia, the AUSTEDO XR or AUSTEDO dose should be reduced; some patients may require discontinuation of therapy.

Parkinsonism: AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO may cause parkinsonism in patients with Huntington’s disease or tardive dyskinesia. Parkinsonism has also been observed with other VMAT2 inhibitors. The risk of parkinsonism may be increased by concomitant use of dopamine antagonists or antipsychotics. If a patient develops parkinsonism, the AUSTEDO XR or AUSTEDO dose should be reduced; some patients may require discontinuation of therapy.

Sedation and Somnolence: Sedation is a common dose-limiting adverse reaction of AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO. Patients should not perform activities requiring mental alertness, such as operating a motor vehicle or hazardous machinery, until they are on a maintenance dose of AUSTEDO XR or AUSTEDO and know how the drug affects them. Concomitant use of alcohol or other sedating drugs may have additive effects and worsen sedation and somnolence.

Hyperprolactinemia: Tetrabenazine elevates serum prolactin concentrations in humans. If there is a clinical suspicion of symptomatic hyperprolactinemia, appropriate laboratory testing should be done and consideration should be given to discontinuation of AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO.

Binding to Melanin-Containing Tissues: Deutetrabenazine or its metabolites bind to melanin-containing tissues and could accumulate in these tissues over time. Prescribers should be aware of the possibility of long-term ophthalmologic effects.

Common Adverse Reactions: The most common adverse reactions for AUSTEDO (>8% and greater than placebo) in a controlled clinical study in patients with Huntington’s disease were somnolence, diarrhea, dry mouth, and fatigue. The most common adverse reactions for AUSTEDO (4% and greater than placebo) in controlled clinical studies in patients with tardive dyskinesia were nasopharyngitis and insomnia. Adverse reactions with AUSTEDO XR extended-release tablets are expected to be similar to AUSTEDO tablets.

Please see accompanying full Prescribing Information, including Boxed Warning.

Costa Mesa, California

This interview with a prominent thought leader in psychiatry explores why it is essential to differentiate between tardive dyskinesia and drug-induced parkinsonism, and he discusses strategies to help clinicians accurately diagnose these disorders.

Q:Why is it important to differentiate between tardive dyskinesia (TD) and drug-induced parkinsonism (DIP)?

A:It is vital to correctly differentiate between TD and DIP because a misdiagnosis and the subsequent inappropriate treatment of one condition can actually aggravate the other condition. That's why it's important to ensure you have an accurate diagnosis before initiating treatment.

TD doesn't appear until a patient has had months or even years of exposure to a dopamine 2 (D2) blocking agent, and the symptomatology is distinct from DIP. Significantly, the pathophysiology of TD is the exact opposite of that of DIP. With TD, patients have too much dopamine in their system. In these cases, the appropriate management would be the use of a vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitor. In fact, an anticholinergic, which is often used to treat DIP, might aggravate the problem. This is why it is so important to differentiate between and accurately diagnose each movement disorder.

With DIP, on the other hand, we encounter abnormal movements in patients shortly after the onset of the use of a treatment that blocks D2 receptors. In the case of DIP, the result of this blockade is that the patient has too little dopamine in his or her system, and in general, the onset of the problem and how to handle it become important issues.

Q:What features can help clinicians differentiate between the two?

A:In terms of symptoms, TD generally presents with more of a hyperkinetic, disjointed movement than does DIP. With TD, the patient's muscle tone is typically well preserved. As we're viewing someone walking, they're going to have a nice arm swing, compared with someone with parkinsonian symptomatology where the arm swing may be diminished. In patients with TD, we see abnormal movements often in the facial or perioral regions. In general, we'll see more emotional affect in patients with TD.

DIP generally presents with typical parkinsonian features, such as lack of movement, slowness, rigidity, stiffness, and/or tremor. Real-world experience suggests that generally a clinician can identify symptoms of DIP, which mimic parkinsonian symptomatology. These symptoms can be readily checked by looking at muscle tone and discovering whether there's some slowness in the patient, ratcheting, cogwheeling, and/or an overall resistance to movement.

It may be surprising to some clinicians that both TD and DIP can coexist in one patient. This comorbidity can further complicate the process of making an accurate diagnosis.

Q:You pointed out that a patient can potentially have both TD and DIP. If a patient does have both, how do you approach treatment?

A:If a patient's predominant movement disorder is DIP, a VMAT2 inhibitor could worsen those symptoms. And treating a patient with TD with an anticholinergic could aggravate the underlying TD. A misdiagnosis can make treatment even more complicated.

When patients have both TD and DIP, the treatment approach can vary, which is why I would encourage the psychiatrist to seek out a second opinion from a movement disorder specialist. Overconfidence should never get in the way of appropriate healthcare delivery. In these complex cases, I always defer to a colleague who has dedicated their life to movement disorders. I typically tell them what I am thinking and then ask if they agree or if they would suggest something different. This process will generally lead to the most appropriate treatment for our complex patients.

Q:From a historical perspective, how has benztropine been used in psychiatry? And what is the appropriate role of benztropine in the management of movement disorders today?

A:Historically, benztropine has been somewhat overutilized in psychiatry. The main reason is that so often when a psychiatrist would see a movement problem, they would automatically think, "Oh, this is a drug-induced movement disorder, so let's throw some anticholinergic at it," which was a mistake. This approach wasn't the result of poor management or lack of care. We didn't have VMAT2 inhibitors, so we thought any medication would be better than nothing. But sometimes using a medication can be counterproductive, which is something we clearly recognize today.

Also, in the past, some clinicians would preemptively prescribe an anticholinergic to patients before making a movement disorder diagnosis, thinking the patients would therefore not get TD or DIP. However, not everyone taking an antipsychotic drug (APD) gets a movement disorder; plus, we now recognize that TD and DIP are distinct disorders that require different therapies. Some clinicians, however, continue to preemptively prescribe anticholinergics, which is part of a mythology we need to overcome through education.

Q:What is currently recommended regarding the use of anticholinergics such as benztropine?

A:If a patient has DIP, the use of benztropine as an anticholinergic is perfectly suitable. However, if TD is suspected, the clinician should not prescribe benztropine, which is stated in the benztropine package insert.

With DIP, as I mentioned, the first step might be simply lowering the dose of the APD being used. Some clinicians may decide to prescribe a different APD to see whether that might clear up the DIP. If these approaches don't work, or if we lose some of the benefit we were getting previously from the APD and we're not willing to absorb weaker efficacy, then the use of an anticholinergic is certainly acceptable. Since we want the anticholinergic to be administered at the lowest possible dose, and for the shortest duration possible, subsequent monitoring of the patient is necessary.

Q:How does VMAT2 inhibition fit into the management of movement disorders?

A:The American Psychiatric Association (APA) recommends using a VMAT2 inhibitor in patients with moderately or severely disabling TD. In patients with mild TD who experience an impact, the APA recommends that physicians consider prescribing a VMAT2 inhibitor. Once the decision to treat TD has been made, the APA recommends VMAT2 inhibitors as first-line therapy, regardless of TD severity.

As I stated earlier, however, it's so important for a clinician to accurately differentiate between TD and DIP so that patients are receiving appropriate treatment. We also know that, as a class, VMAT2 inhibitors carry certain warnings; among them is the possibility of parkinsonian symptoms. So, there's a chance we could overtreat somebody with a VMAT2 inhibitor. That's why it's important to treat patients with the most appropriate therapy based on an accurate diagnosis.

Q:How much progress have we made in educating psychiatrists to not preemptively use anticholinergics and to diagnose accurately?

A:We are aware that there are currently approximately 785,000 people with TD. The sad thing is that fewer than a quarter of individuals with TD are actually diagnosed. What's even sadder is that less than 1 out of 10 people are actually treated for a condition for which they could receive treatment. We need to remind clinicians that they must proactively look for and do something about this problem.

We've tried to counter that inertia through educational forums and, more generally, through speaking openly about the current landscape of TD. Yet, we still haven't reached that tipping point where clinicians just automatically use every opportunity given to them to look for TD and effectively counter it. So, we must continue to proactively educate our peers.

When clinicians make the argument that patients receiving the atypical D2-blocking APDs have a much lower risk of developing TD than those taking typical APDs, my response is this: the atypical APDs still carry a risk. The wide dissemination of APDs for conditions that stretch beyond schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are certainly leading to the tremendous growth of the overall number of patients exposed to these medications. And so, we need to stay ahead of the curve.

Q:Is there anything else you'd like to add?

A:I think it is critical for us to advocate for our patients. We need to give individual patients a voice and help them understand that if they have TD, it can be dealt with. In the past, not having a solution to the challenge of TD meant that individuals would have to try to ignore their TD by brushing it under the rug and suffering in silence. We are fortunate that we don't have to do that anymore—we are well equipped to take positive action in helping patients with TD.

Bhidayasiri R, Jitkritsadakul O, Friedman JH, Faun S. Updating the recommendations for treatment of tardive syndromes: a systematic review of new evidence and practical treatment algorithm. J Neurol Sci. 2018;389:67-75. Caroff SN. Overcoming barriers to effective management of tardive dyskinesia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:785-794. Caroff SN, Campbell EC. Drug-induced extrapyramidal syndromes: implications for contemporary practice. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(3):391-411. Estevez-Fraga C, Zeun P, Lopez-Sendon Moreno JL. Current methods for the treatment and prevention of drug-induced parkinsonism and tardive dyskinesia in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2018;35(11):959-971. Factor SA, Burkhard PR, Caroff S, et al. Recent developments in drug-induced movement disorders: a mixed picture. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(9):880-890. Hauser RA, Meyer JM, Factor SA, et al. Differentiating tardive dyskinesia: a video-based review of antipsychotic-induced movement disorders in clinical practice. CNS Spectr. 2022;27(2):208-217. Perju-Dumbrava L, Kempster P. Movement disorders in psychiatric patients. BMJ Neurol Open. 2020;2(2):e000057. Rekhi G, Tay J, Lee J. Impact of drug-induced parkinsonism and tardive dyskinesia on health-related quality of life in schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol. 2022;36(2):183-190. Ward KM, Citrome L. Antipsychotic-related movement disorders: drug-induced parkinsonism vs. tardive dyskinesia—key differences in pathophysiology and clinical management. Neurol Ther. 2018;7(2):233-248.