Managing a patient with an ongoing mental health condition can be challenging but rewarding work for nurse practitioners (NPs). But imagine that same patient develops uncontrollable movements because of the treatment for their mental health condition. It is important to focus on the patient's mental health, but now, the added burden of an unwelcome movement disorder must also be addressed.

NPs who work in psychiatry and treat patients with tardive dyskinesia (TD) may frequently find themselves in this situation. In this article, we will discuss how NPs can play a key role in managing care for their patients with TD. This includes knowing what to look for and why it is important to screen and assess at every visit, developing treatment plans to meet each patient's individualized needs, and understanding the impact that TD can have on patients and their families and caregivers.

TD is a persistent, typically irreversible, involuntary movement disorder associated with prolonged exposure to antipsychotic drugs (APDs).1-3 With use of atypical APDs expanding beyond patients with schizophrenia to include patients with major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder, more patients may be at risk for developing TD.3 In fact, in 2022, about 8.7 million patients were being treated with APDs.4

However, TD may be underdiagnosed and undertreated. A recent estimate suggests that TD affects approximately 785,000 patients in the United States.4 However, approximately 15% of patients with TD have received a formal diagnosis, and less than 6% of patients have been treated with vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors.4

Underdiagnosis and undertreatment of TD can have profound consequences for patients because TD can substantially impact many aspects of patients' lives, including their ability to perform daily activities, be productive, and socialize.5 TD also can make their underlying mental health condition harder to manage, as patients have reported lack of adherence to their APD regimen because of their TD.5 A survey found that 3 out of 4 patients reported a severe impact of TD on their daily lives, leading to functional disability.5

When assessing a patient for TD, there are a few key features to note:

| • | Delayed onset—symptoms associated with TD usually appear after at least 3 months of treatment with an APD, although sometimes in older patients, symptoms appear as quickly as 1 month1 |

| • | Movements associated with TD can be rapid and jerky, sinuous, or semirhythmic. This is a distinct difference from the rhythmic tremors commonly seen with medication-induced parkinsonism1 |

| • | TD most often involves the face, mouth, tongue, and jaw. Common movements in this area include teeth grinding, twisting or curling of the tongue, puckering or pursing of the lips, grimacing, and excessive eye blinking6 |

| • | In addition to the face, patients with TD may show symptoms on any part of their body, including the trunk, arms, and legs (Videos 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3)6 |

No clinical studies have been conducted to evaluate the effects of treating TD on the impact outcomes discussed in this article.

All patients taking APDs should be screened and assessed for movements and their impact at every clinical encounter. This can be accomplished through a combination of semistructured exams and structured assessments, such as the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS).3,7,8

Any presentation of TD, regardless of severity, can impact patients (Videos 1.4, 1.5, 1.6, and 1.7).8,9 Gauging the impact of TD for each patient is subjective and depends on individual circumstances.8 Even small movements can cause anxiety and disrupt the patient's day-to-day life in many ways, such as talking, walking, and eating or drinking—even breathing.8 The way that TD affects each patient is key in the decision to start treatment.8

TD can cause disability through its impact on various aspects of a patient's life, including their psychological, social, physical, and vocational well-being.10 In a recent survey, 75% of patients reported that TD had a severe impact on their daily lives,5 which may include loss of friendships and romantic relationships and an increase in social avoidance and withdrawal from relationships.11,12 Even mild TD symptoms can negatively affect a patient's quality of life, as shown by the fact that 62% of patients with no, mild, or moderate TD symptoms reported severe impact. That figure increased to 95.4% for patients with severe or very severe TD symptoms.5 It is also important to note that even mild TD symptoms can lead others to view the patient as less friendly or less suitable for client-facing work or romantic situations.11

Patients may report a wide range of issues related to their TD, including worsening depression, social withdrawal, physical symptoms such as pain, impaired work performance, or inability to participate in hobbies.5 Staying aware of these symptoms and working with patients to manage symptoms effectively is a vital role NPs can play in caring for these patients.

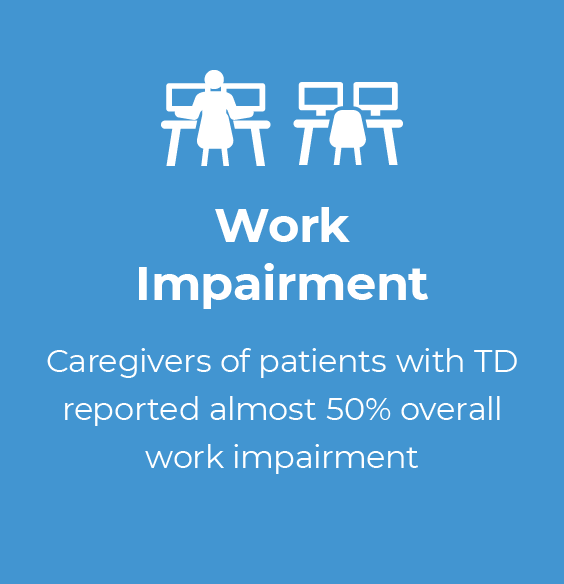

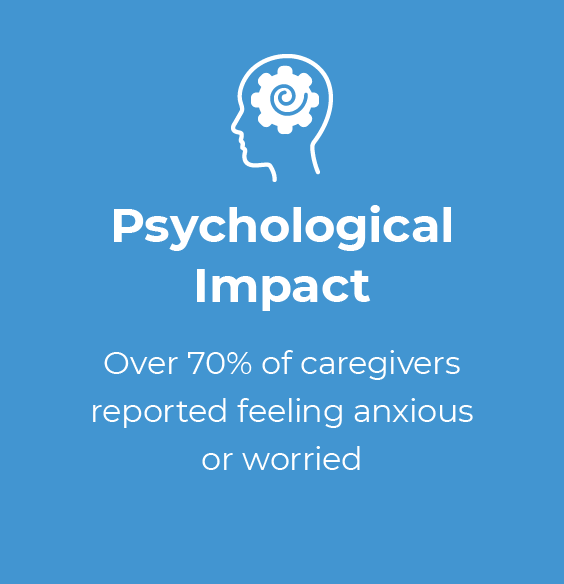

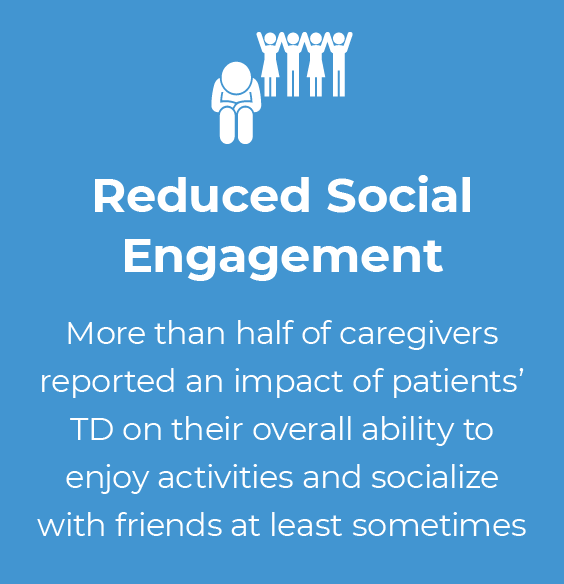

Supporting patients with TD can have an impact on caregivers' own activities and well-being (Figure 1.1).13 Caregivers reported impairment at work, including missed workdays and difficulty while working, feeling anxious or worried about the patient in their care, and less enjoyment from being with friends.13 In fact, nearly 1 in 4 caregivers who responded to a recent survey reported severe impact of the patient's TD on their own functioning and well-being.13

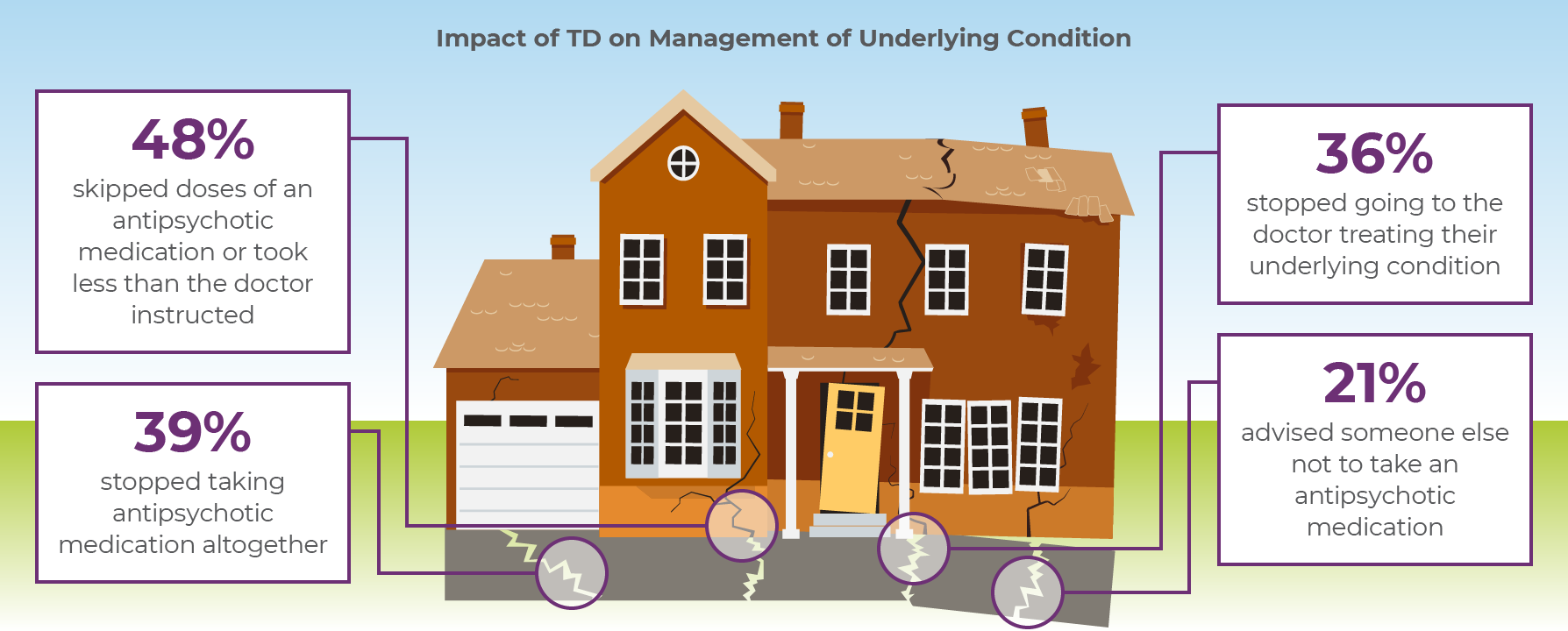

TD can also impact the clinician's ability to manage the patient's ongoing mental health condition (Figure 1.2). In a recent survey of patients with TD5

| • | 48% skipped doses of APDs or took less than was prescribed because of their TD |

| • | 39% stopped taking their APDs altogether |

| • | 36% stopped going to the doctor to treat their condition |

| • | 21% advised other patients to stop taking their APDs |

Consider that this may also undermine the stability of the patient's long-term mental health.

It is essential to consider the impact of TD when making treatment decisions.8 Even small movements associated with TD can have a significant impact on the patient's daily life, which is why the American Psychiatric Association Guidelines recommend appropriate treatment for TD if it has any impact on the patient, regardless of severity.7,8

However, the routine assessment of TD in clinical practice is often lacking, despite its potential to profoundly impact patients' lives.8 To address this gap, a consensus panel of clinicians with experience in treating TD and/or conducting TD research, supported by an unrestricted grant from Teva, developed the Impact-TD scale. This tool can be used to assess the functional impact of TD across 4 domains14:

| • | Psychological/psychiatric |

| • | Social |

| • | Physical |

| • | Vocational/educational/recreational |

The Impact-TD scale is an easy-to-use clinical scale that can help NPs assess how TD may affect their patients' lives. It was developed for a wide range of healthcare providers and can be helpful in establishing the assessment of TD impact as part of the standard of care for patients with TD. The scale's use could increase awareness of TD and TD treatment, leading to better management of TD and improved patient outcomes.14

Managing ongoing mental health conditions in patients can become more challenging when they also experience TD. Patients may choose to reduce their dose or even stop taking APDs altogether when TD symptoms begin to interfere with their daily lives.5 It is essential to note that even mild symptoms of TD can significantly impact a patient's life, despite the patient not reporting them as bothersome.8,9 Consequently, assessment of impact should be a routine part of clinical practice.8

Moderate to severe or disabling TD should be treated with a VMAT2 inhibitor. Mild TD should be considered for treatment if it has an impact on the patient's psychosocial functioning or associated impairment, or if the patient's preference is to receive treatment for TD.7

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a movement disorder that can develop in patients taking both typical and atypical antipsychotic drugs (APDs).1 It is often underdiagnosed and undertreated and can negatively impact patients' lives.2-4 As a result, patients taking APDs should be assessed for movements associated with them and their impact at every clinical encounter.5,6 In this article, we will discuss how nurse practitioners (NPs) can uphold this standard of care for all patients taking APDs, including those who develop TD, by routinely monitoring for the presence of movements and assessing the severity and impact of TD in clinical practice.

It is essential to be aware of the risk of TD associated with APDs and to communicate these risks to patients on a routine basis.6 The use of APDs has substantially increased over the past decades, with estimates suggesting a nearly 300% increase, from 2.2 million patients in 1997 to 8.7 million patients in 2022, based on the expanded indication of APDs from schizophrenia (first approval in 1989) to mood disorders.2,7-11 Prevalence of TD in the United States is increasing, with current estimates of ~785,000 affected individuals.2 However, only ~15% of patients with TD have received a formal diagnosis, and <6% of patients are being treated with vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors, suggesting that TD is likely underdiagnosed and undertreated.2 The reported prevalence of TD among patients taking APDs varies but is approximately 30% among patients receiving typical APDs and 7% among patients receiving atypical APDs.12 Age and cumulative exposure to APDs (eg, dose, length of exposure, potency) are factors that may increase the risk of TD.6 The increased use of APDs over the past decades necessitates vigilance among NPs in psychiatry in screening for TD in all patients taking APDs so they may provide appropriate care for these patients.2,6,7

Importantly, TD can have a significant impact on patients' lives, impairing their day-to-day functions and negatively affecting their quality of life.3,4 By properly screening for and assessing TD, and providing appropriate treatment, NPs can help uphold the standard of care for their patients.

The Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) is the standard structured assessment for screening for and monitoring the severity of TD.6 This assessment can help you identify any abnormal movements or motor symptoms that may be indicative of TD.13-15 It is important to perform this assessment regularly, as TD can develop over time even in patients who have been taking APDs for years.6

As recommended by the American Psychiatric Association (APA), all patients initiating APD treatment should undergo a structured assessment, such as the AIMS exam, given the lifelong risk of developing a subsequent movement disorder.13 Patients at high risk of TD should undergo an AIMS assessment every 6 months, while other patients should be assessed with the AIMS at least every 12 months. Additionally, an AIMS exam should be performed if any new onset or exacerbation of preexisting movements is detected during a clinic visit.13

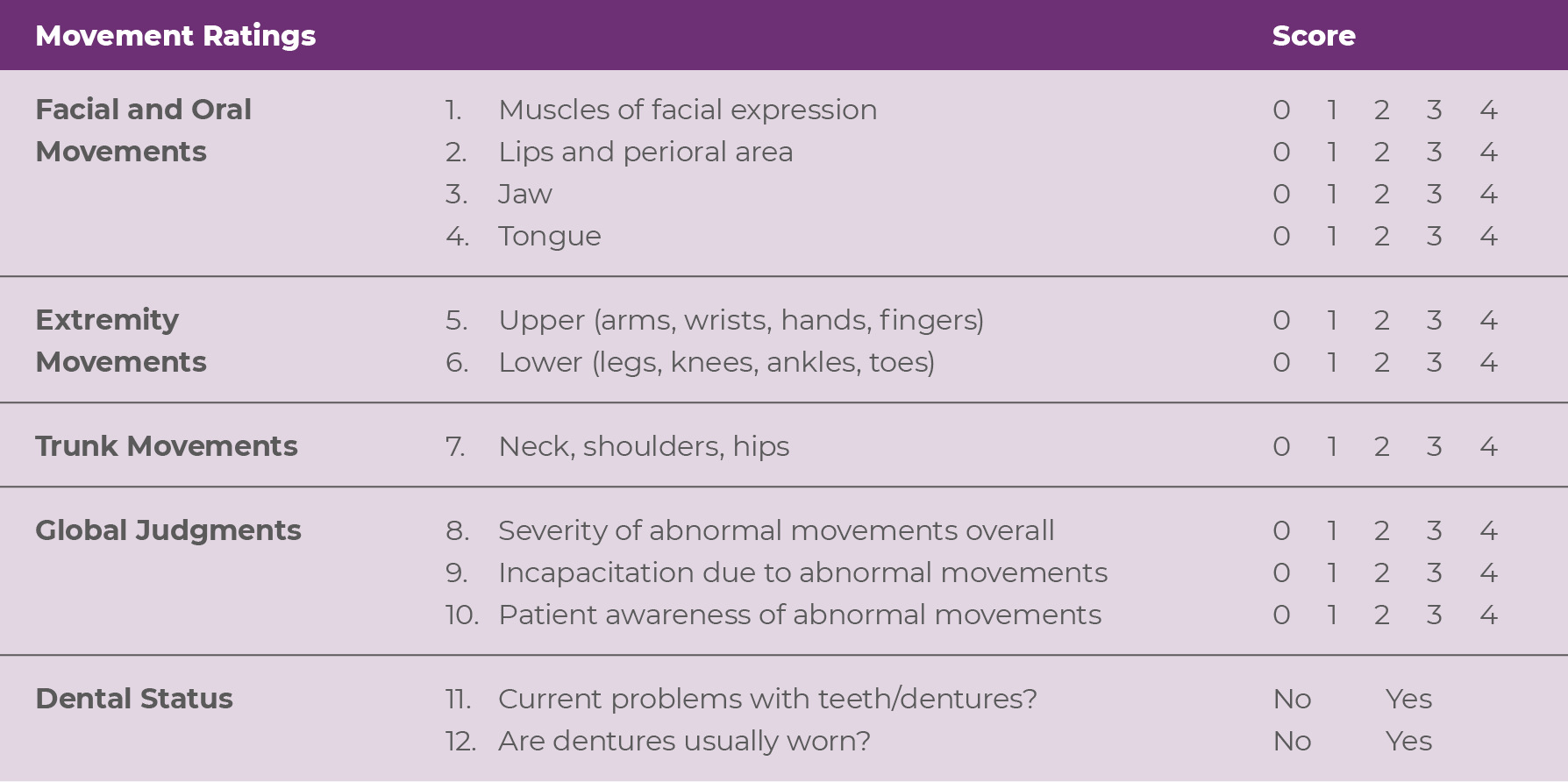

The AIMS is a broad, multipurpose tool that enables NPs in psychiatry to screen for abnormal movements in a systematic fashion, to assess the severity of abnormal movements, and to monitor any changes in movements over time or with treatment.14,16 In addition to providing instructions for a visual examination and verbal inquiries around abnormal movements, the AIMS also describes how to rate, or score, what is observed.14 The 12-item AIMS includes assessment of the severity of involuntary movements across body regions, as well as a global severity score, patient awareness and distress, and dental issues (Figure 2.1).14

Each of the first 7 items is scored on a 0 to 4 scale, rated as: 0=none, not present; 1=minimal, may be extreme normal (abnormal movements occur infrequently and/or are difficult to detect); 2=mild (abnormal movements occur infrequently and are easy to detect); 3=moderate (abnormal movements occur frequently and are easy to

detect); or 4=severe (abnormal movements occur almost continuously and/or are of extreme intensity).14,15

Each of the first 7 items is scored on a 0 to 4 scale, rated as: 0=none, not present; 1=minimal, may be extreme normal (abnormal movements occur infrequently and/or are difficult to detect); 2=mild (abnormal movements occur infrequently and are easy to detect); 3=moderate (abnormal movements occur frequently and are easy to

detect); or 4=severe (abnormal movements occur almost continuously and/or are of extreme intensity).14,15

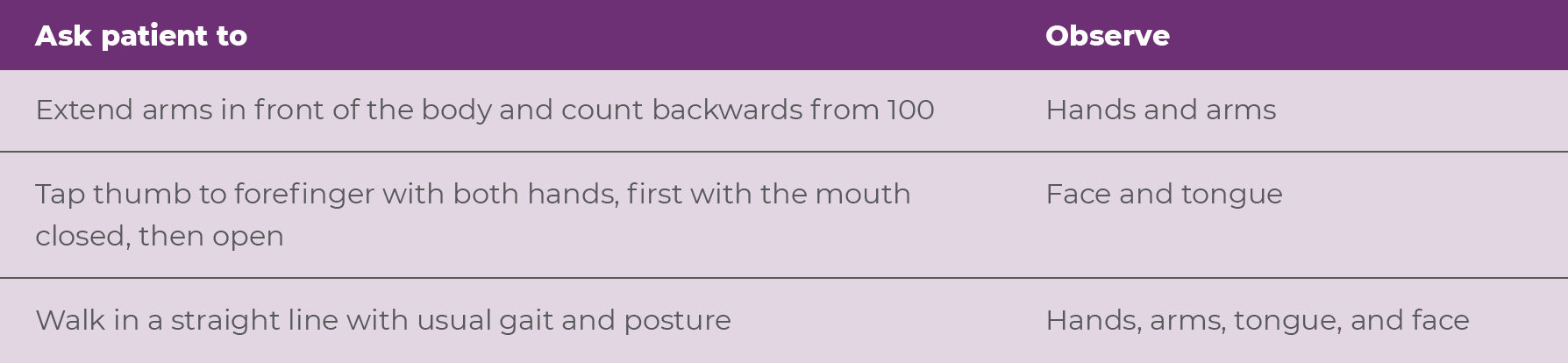

Since patients can temporarily mask their movements in the setting of a formal examination, the NP can make the most of the appointment by purposefully assessing the patient for movements throughout the entirety of the patient visit.15 For instance, carefully examining the patient during the walk from the waiting room to the NP's office and during a routine clinical interview may help reveal abnormal movements that don't appear during a formal examination.15 Activation maneuvers are another technique providers may use to help avoid a patient masking their movements, as these activations can elicit involuntary movements in one area of the body while the patient is focused on performing a task with a different body part.15 Activation maneuvers can incorporate both physical and cognitive tasks (Table 2.1, Video 2.1).16

It is essential that every patient receiving APDs is assessed for movements at every visit.6 A routine assessment at every visit allows for a better evaluation of how symptoms of TD, and the impact they may have on a patient's life, vary over time, which ultimately will drive treatment decisions.5 Routine assessment is feasible for patients with, or at risk of developing, TD at every clinic visit through the use of a semistructured exam.6

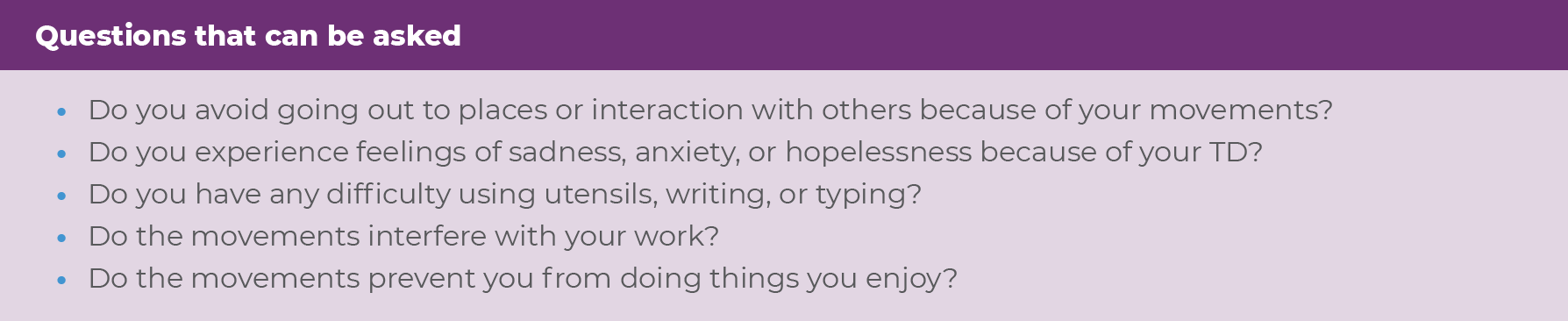

A semistructured assessment should be informed by a baseline AIMS exam conducted at initiation of treatment with the APD and should include asking about and observing abnormal movements.6,13 During a semistructured exam, the NP may ask about whether the patient has noticed any movements, as part of a routine review of the side effects of their medication, empowering the patient to play an active role in their care.6 The NP may pose clinically meaningful, directed questions to the patient, ultimately seeking to answer “What bothers you the most?” and involving family members or caregivers in the assessment process.6,16 It is important to keep in mind that patients may not be forthcoming when reporting their symptoms of TD, so involving family members and caregivers can help identify any onset or changes in symptoms that may otherwise remain unreported.5 Activation maneuvers may also help to unmask movements during a semistructured exam.16 Any new or worsened symptoms detected during a routine assessment would suggest the need for a full AIMS assessment.13

If movements are present, it is important to assess not only severity but also the impact of movements at every visit.5 Keep in mind that even small movements can have a major impact, depending on the individual circumstances of the patient.5 Seemingly minor issues can result not only in social anxiety but also problems with daily activities, including eating, speaking, breathing, and ambulation.5 Understanding the impact of TD on a patient should drive the shared decision to treat TD as well as the urgency with which treatment should be initiated.5 Further, APA guidelines recommend that TD be treated appropriately if it has an impact on the patient, regardless of severity.13

Assessment of the impact of TD may be facilitated by the Impact-TD scale, a short, easy-to-administer checklist to uncover impact developed by a panel of independent experts in psychiatry and movement disorder neurology (Figure 2.2).4

The Impact-TD scale is discussed in more detail in Article 1 of this volume.

The Impact-TD scale is discussed in more detail in Article 1 of this volume.

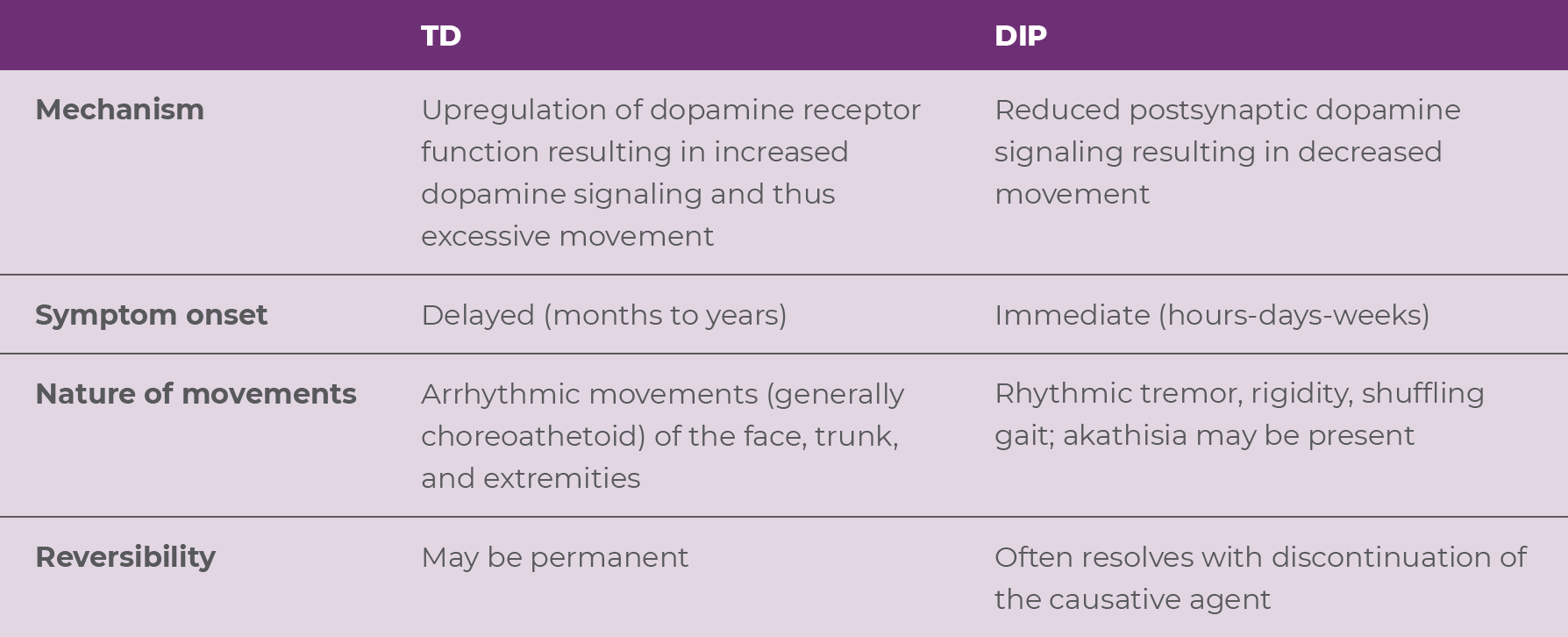

TD and drug-induced parkinsonism (DIP) represent 2 of the most common movement disorders associated with use of APDs.20 TD and DIP are separate clinical entities, with unique underlying mechanisms and clinical manifestations (Table 2.2).1,18 Importantly, differentiation of these disorders is essential, as treatment for one disorder can worsen the other.1,18 DIP is caused by a reduction in postsynaptic dopamine signaling, due to an acute blockade of dopamine receptors via the mechanism of some APDs.18 As a result, the onset of DIP occurs immediately (hours-days-weeks) after starting or increasing the dose of an APD.18 In contrast, while not fully understood, TD is believed to be caused by upregulation of dopamine signaling due to a chronic blockade of dopamine receptors (via APDs), resulting in excessive movement.1,18 As a result, the onset of TD is delayed, often occurring months to years after APD use.18

TD and DIP are distinct and relatively easy to differentiate. TD is characterized by an excess of movements that are irregular, jerky, and unpredictable and are accompanied by normal muscular tone (Video 2.2).19,21,22 On the other hand, DIP is characterized by a paucity of movement. When movements occur, they are typically rhythmic and may be accompanied by rigidity (Videos 2.3 and 2.4).22,23

It's crucial to differentiate between these two disorders, as they require different treatment approaches, and treatment for one disorder can worsen the other.18,19 Although discontinuing the APD may improve or resolve the symptoms associated with DIP, APD reduction or discontinuation may fail to improve the symptoms of TD and might even induce withdrawal dyskinesia.19 Importantly, while anticholinergics are indicated for the treatment of DIP, these drugs can worsen TD symptoms.18,19 In fact, both the APA treatment guidelines and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision, caution against using anticholinergics to treat TD.13,19 Moreover, the prescribing information for benztropine, a commonly used anticholinergic, warns that antiparkinsonian agents do not alleviate the symptoms of TD and may, in some instances, aggravate them.24 Lastly, VMAT2 inhibitors are recommended for adults with TD, but it should be noted that they can worsen parkinsonism.18,19

By monitoring for the presence of movements and, if movements are detected, assessing the severity of TD symptoms and their impact on the patient at every clinical encounter, NPs can uphold the standard of care for all patients taking APDs.5,6 Routine assessment can be accomplished in clinical practice by performing structured (AIMS) assessments at APA-recommended intervals and semistructured assessments at all visits in between.6,13 The APA recommends treating TD appropriately if it has any impact on the patient, regardless of the severity.13 It is necessary to differentiate TD from other medication-induced movement disorders, such as DIP, because each disorder requires a different treatment approach.18,19 Understanding the differences between TD and DIP and the appropriate treatment approaches for each will enable you to provide the best care for your patients.

References

All patients taking antipsychotic drugs (APDs) are at risk of developing tardive dyskinesia (TD), which can substantially impact various aspects of patients' lives and complicate the management of the underlying mental health disorder.1-5 The American Psychiatric Association (APA) guidelines recommend vesicular monoamine transport type 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors as first-line treatment for TD, regardless of severity.6 For patients with moderate to severe or disabling TD associated with antipsychotic therapy, the APA recommends treatment with a reversible inhibitor of VMAT2. The APA guidelines further recommend considering a VMAT2 inhibitor to address TD-associated impairments and impact on social functioning.6 VMAT2 inhibitors are recommended for TD without requirement to modify the APD dose.6,7 This article provides nurse practitioners (NPs) with information on AUSTEDO XR, a one pill, once-daily treatment for adults with TD.

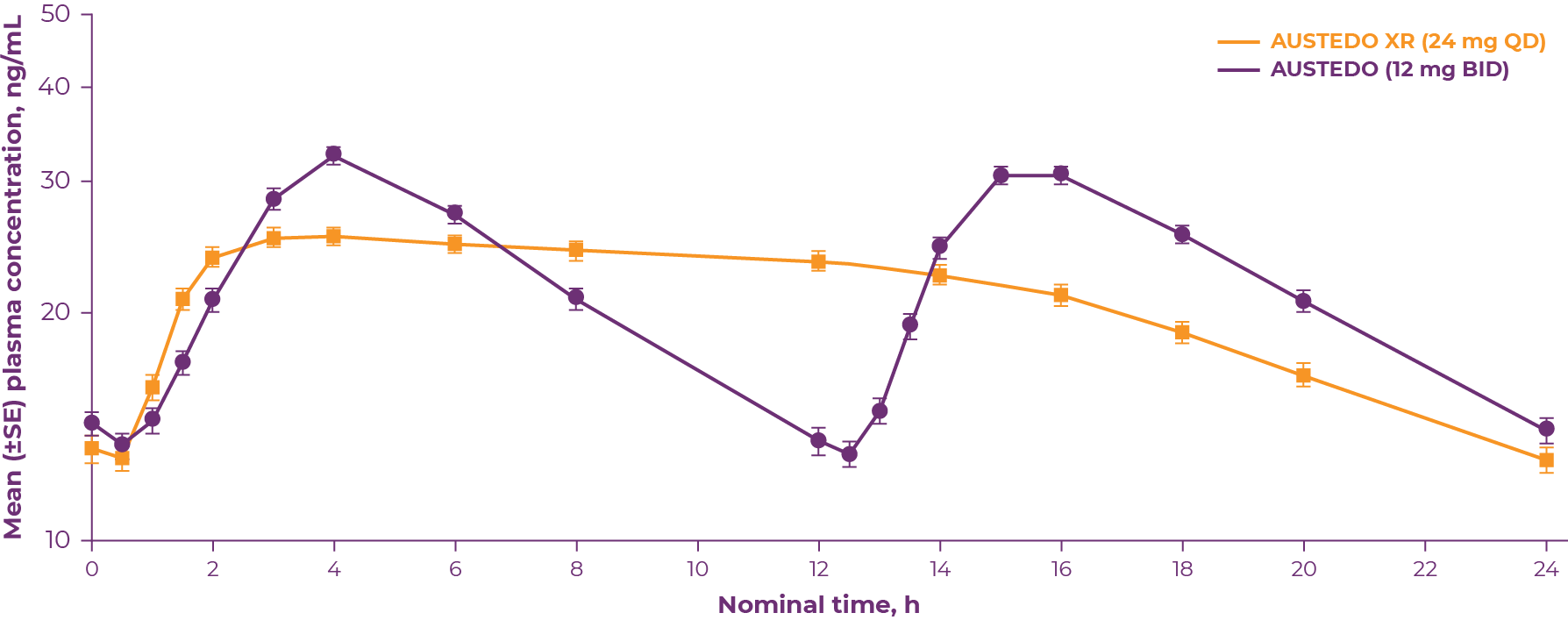

Once-daily AUSTEDO XR is a VMAT2 inhibitor approved in adults for the treatment of TD.7 The US Food and Drug Administration defines bioequivalence as the absence of a significant difference in the drug exposure profile of 2 drugs. When 2 formulations are shown to be bioequivalent, they can be considered therapeutically equivalent.8 Bioequivalence of AUSTEDO XR has been established with AUSTEDO® (deutetrabenazine) tablets BID based on pharmacokinetic profile studies performed across 3 phase 1 clinical trials in healthy volunteers. Data support equivalence of AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO BID across the full clinical dosing range (12 mg QD to 48 mg QD). In the bioequivalence study, peak plasma concentrations (Cmax) of AUSTEDO XR were reached within approximately 3 hours followed by a sustained plateau during the majority of the 24-hour dosing interval (Figure 3.1).9

*Bioequivalence was determined by the plasma concentration-time curve from time 0-24 h at steady state of deutetrabenazine (parent) and deuterated α-dihydrotetrabenazine and β-dihydrotetrabenazine metabolites.

*Bioequivalence was determined by the plasma concentration-time curve from time 0-24 h at steady state of deutetrabenazine (parent) and deuterated α-dihydrotetrabenazine and β-dihydrotetrabenazine metabolites.

Because bioequivalence between AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO BID has been established, it can be reasonably expected that the efficacy and safety in adults with TD treated with AUSTEDO XR will be similar to what has been demonstrated in the clinical trials with the AUSTEDO BID formulation.8 The ARM-TD, AIM-TD, and RIM-TD clinical trials were conducted to assess efficacy and safety of AUSTEDO in patients with TD.10-12 Patients in these clinical trials received the AUSTEDO BID formulation.

ARM-TD was a flexible-dose clinical trial in which patients' doses were individually titrated to a level that reduced abnormal movements and was tolerated.7,11 Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive AUSTEDO or placebo. The starting dose of AUSTEDO was 12 mg/day, which was increased by 6 mg/day each week until satisfactory control of TD was achieved, until intolerable side effects occurred, or until a maximal dose of 48 mg/day was reached. Patients were titrated to an optimal dose over 6 weeks. The 12-week treatment period included this 6-week titration period and a 6-week maintenance period and was followed by a 1-week washout.7,11

The primary efficacy endpoint for this study was the change from baseline (defined for each patient as the value from the day 0 visit) to Week 12 in Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) total score (sum of items 1 through 7) as assessed by 2 blinded central video ratings.8,11 Higher AIMS scores are indicative of more severe dyskinesia. Patients in the ARM-TD study showed a significant improvement in AIMS total score from baseline at Week 12 vs placebo (3.0-point reduction vs 1.6-point reduction; P=0.019).8,11

AIM-TD was a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose trial in which patients were randomized 1:1:1:1 to placebo or AUSTEDO 12 mg, 24 mg, or 36 mg.7,10 Treatment duration included a 4-week dose-escalation period and an 8-week maintenance period followed by a 1-week washout. The dose of AUSTEDO was started at 12 mg/day and increased at weekly intervals in 6-mg/day increments to a dose target of 12, 24, or 36 mg/day.7,10 The primary efficacy endpoint was change from baseline to Week 12 in AIMS total score in the 36-mg/day group versus placebo, assessed by blinded central video rating.7,8,10 In AIM-TD, AUSTEDO significantly reduced AIMS total score by 3.3 points from baseline in the 36-mg/day arm (versus a reduction of 1.4 points with placebo) at Week 12 (P=0.001, treatment effect of −1.9 points).7,10 In an exploratory analysis, significant AIMS total score reduction was seen at 2 weeks for the 24- and 36-mg/day groups.10

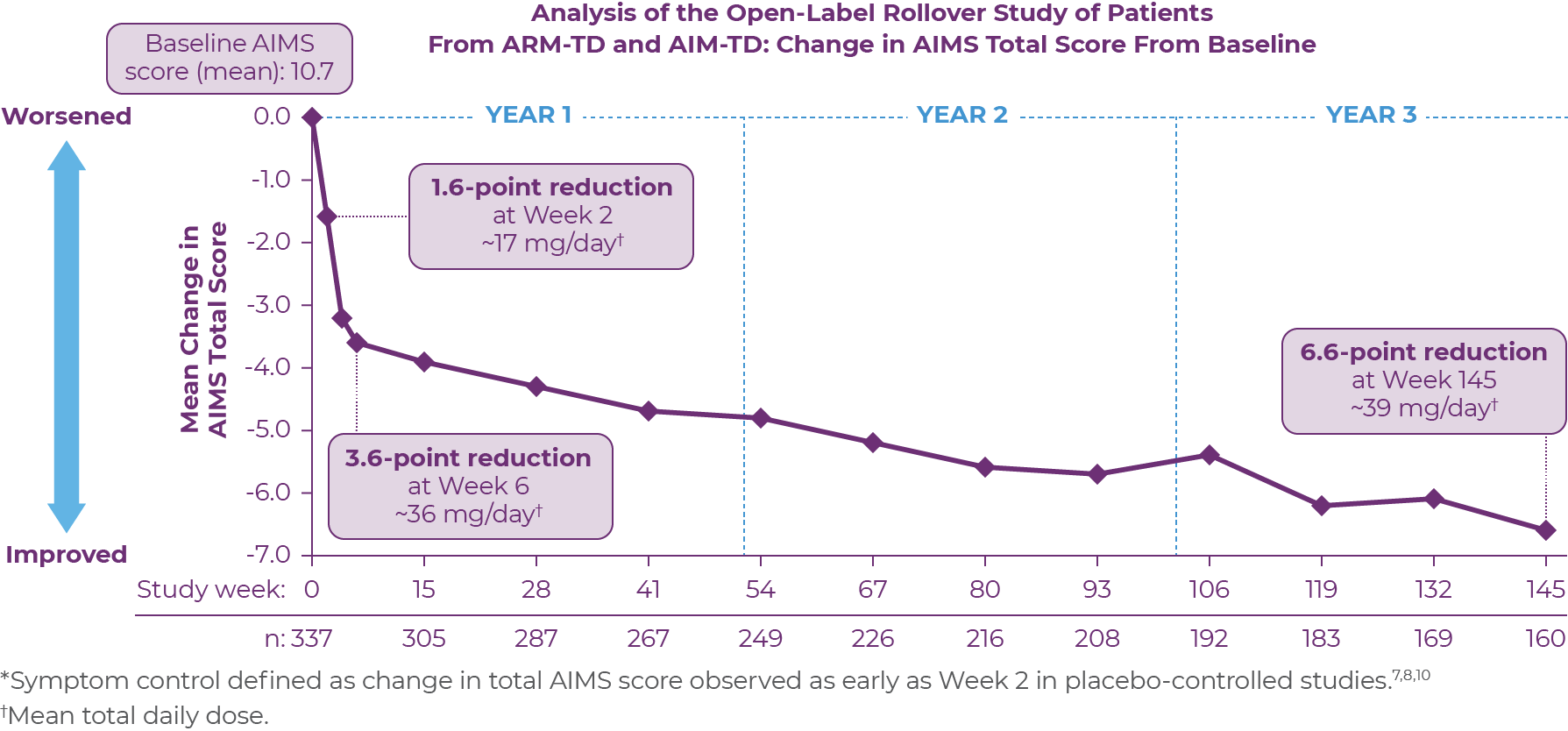

RIM-TD was an open-label, long-term maintenance study in patients who successfully completed ARM-TD or AIM-TD.12 Patients discontinued AUSTEDO for 1 week and then started at a dose of 12 mg/day, which was titrated for up to 6 weeks. The dose was increased in a response-driven manner on a weekly basis by 6 mg/day until either the maximum allowable dose was reached, a clinically significant adverse event (AE) occurred, or adequate dyskinesia control was achieved. Patients were followed for approximately 3 years (145 weeks).12

Among the patients evaluated, 337 patients had treatment at baseline and 160 patients had treatment through the end of week 145.12 During the overall treatment period, patients generally experienced an improvement in the AIMS total score. There was a gradual reduction in the mean AIMS total scores from baseline through Week 145 (Figure 3.2). The average dose of AUSTEDO was >36 mg/day (39.4 mg/day at Week 145).12

Patients in the RIM-TD study received the AUSTEDO BID formulation.

Patients in the RIM-TD study received the AUSTEDO BID formulation.

At Week 145 in RIM-TD, 67% of patients achieved ≥50% improvement in AIMS total score.12 Clinicians and patients generally recognized improvement in TD symptoms with AUSTEDO treatment based on assessments of Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGIC) and Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) over time. At Week 145, a majority of patients (63%) and physicians (73%) reported symptoms as “much improved” or “very much improved.”12 Preexisting psychiatric scores remained stable throughout the treatment period, and AEs were comparable to those seen in the clinical trials.8,12 The mean overall compliance rate was nearly 90% at 3 years.8

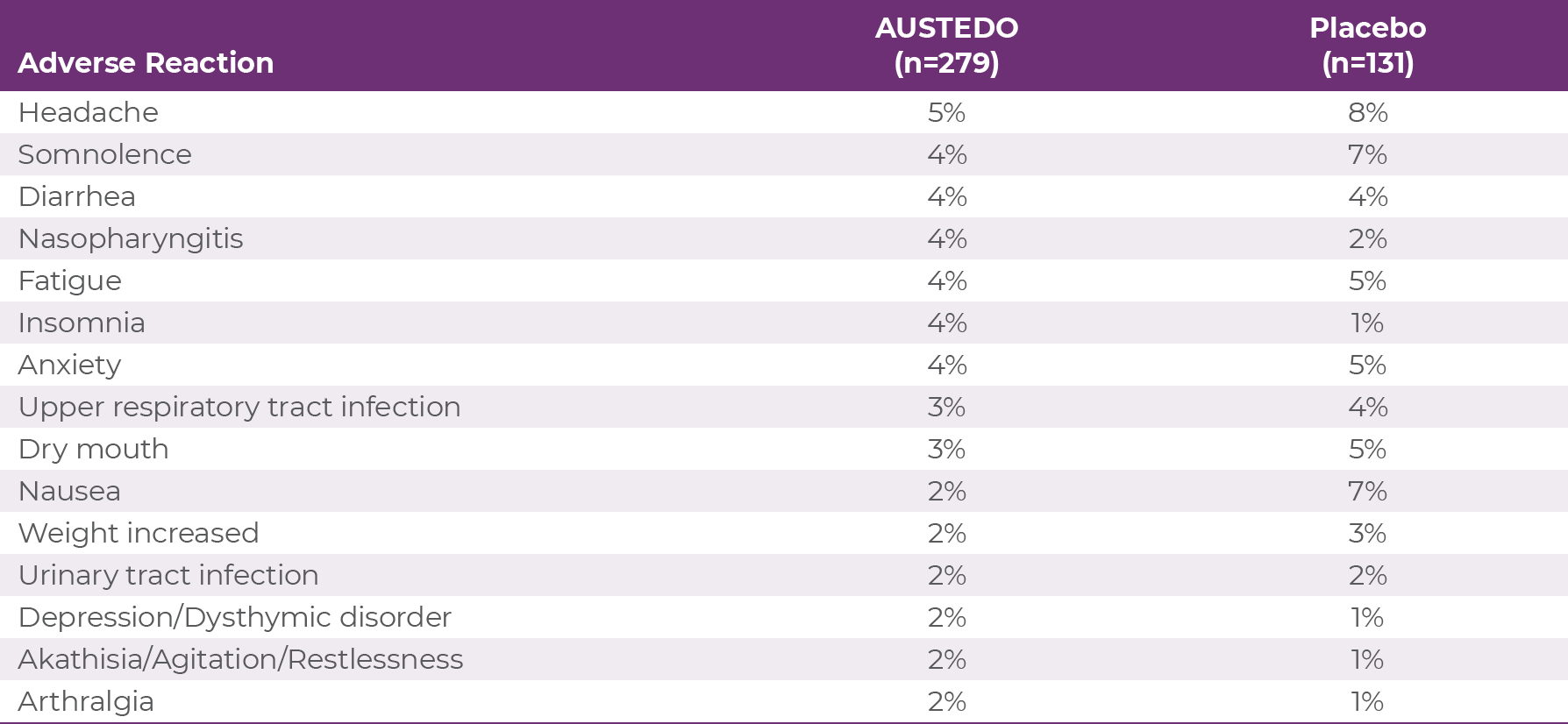

The most commonly reported adverse effects by patients treated with AUSTEDO (3% and greater than placebo) in the placebo-controlled studies were nasopharyngitis and insomnia (Table 3.1).7 Discontinuation due to AEs occurred in 4% of patients taking AUSTEDO vs 3% of patients taking placebo.10,11 Dose reduction due to AEs was required in 4% of patients taking AUSTEDO vs 2% of patients taking placebo.7 Adverse reactions with AUSTEDO XR are expected to be similar to the AUSTEDO BID formulation.7

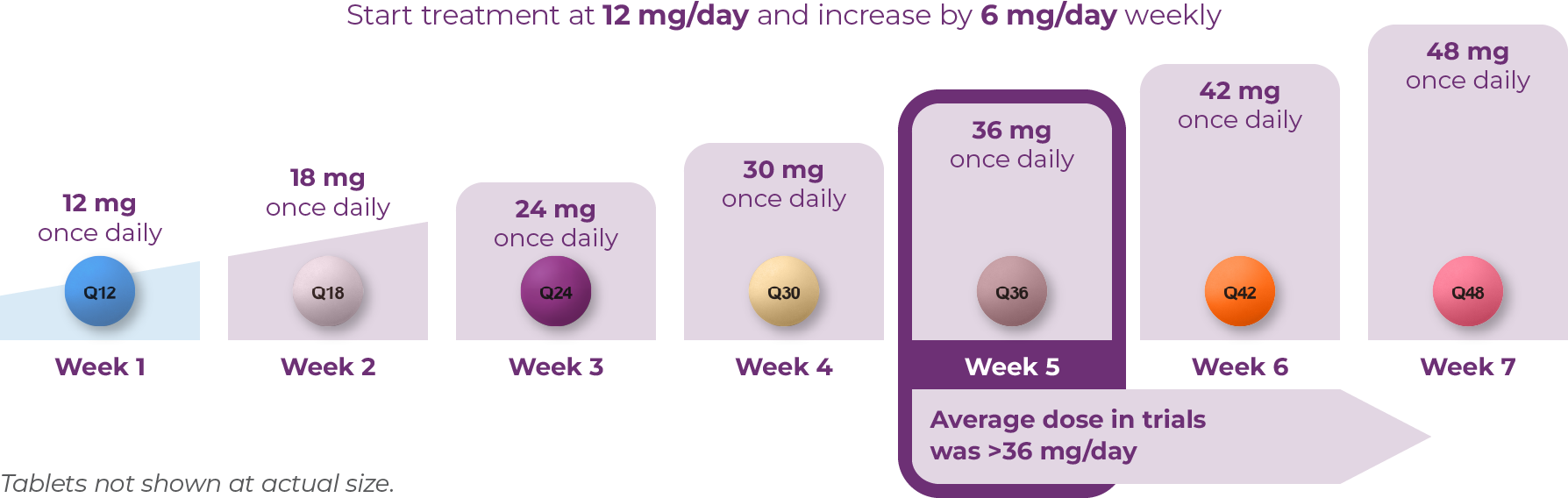

AUSTEDO XR is available in 12 mg, 18 mg, 24 mg, 30 mg, 36 mg, 42 mg, and 48 mg extended release tablets, providing flexibility for effective and tolerable symptom control.

The recommended starting dose for AUSTEDO XR for patients with TD is 12 mg/day. The dose should be increased weekly by 6 mg/day until symptom control is tolerably achieved (Figure 3.3).7 The average daily dose in clinical trials was >36 mg/day.10-12 This average dose emphasizes the importance of titration when appropriate to help patients achieve desired symptom control.

Once-daily AUSTEDO XR can be taken with or without food.7 AUSTEDO XR should be swallowed whole. Tablets should not be chewed, crushed, or broken.7 The maximum recommended daily dose of AUSTEDO XR is 48 mg.7

AUSTEDO XR is the only VMAT2 inhibitor indicated for TD with no recommendations against concomitant use with CYP3A4/5 inducers or inhibitors.7,13 AUSTEDO XR is metabolized primarily through CYP2D6, with minor contribution of CYP3A4/5 and other enzymes to form several minor metabolites.7 The maximum recommended dosage for patients who are taking strong CYP2D6 inhibitors or those who are poor CYP2D6 metabolizers is 36 mg/day.7AUSTEDO XR is the VMAT2 inhibitor with the most once-daily doses for these patients.7,13

AUSTEDO XR can be administered without the need to reduce the APD, enabling NPs to treat TD without having to alter patients' currently established regimens and risk destabilizing their underlying mental health condition.7

AUSTEDO XR is a one pill, once-daily medication indicated in adults for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia.7 In the clinical studies with AUSTEDO BID, patients achieved rapid symptom control, defined as a change in total AIMS score as early as Week 2 in the placebo-controlled studies, with sustained results observed through ~3 years.7,10-12 The most common AEs for AUSTEDO (3% and greater than placebo) in controlled studies in patients with TD were nasopharyngitis and insomnia.7 Bioequivalence of once-daily AUSTEDO XR was established with AUSTEDO BID based on pharmacokinetic profile studies.8 When 2 formulations are shown to be bioequivalent, they can be considered therapeutically equivalent.9 Efficacy and adverse reactions with AUSTEDO XR are expected to be similar to AUSTEDO BID.7,9 With AUSTEDO XR, you can offer your patients the opportunity to achieve tolerable symptom control over the long term without disrupting their current APD treatment regimen and undermining the stability of their underlying mental health disorder.7

1. Carbon M, Hsieh CH, Kane JM, Correll CU. Tardive dyskinesia prevalence in the period of second-generation antipsychotic use: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(3):e264-e278. 2. Caroff SN, Yeomans K, Lenderking WR, et al. RE-KINECT: a prospective study of the presence and healthcare burden of tardive dyskinesia in clinical practice settings. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;40(3):259-268. 3. Jackson R, Brams MN, Citrome L, et al. Assessment of the impact of tardive dyskinesia in clinical practice: consensus panel recommendations. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:1589-1597. 4. Ascher-Svanum H, Zhu B, Faries D, et al. Tardive dyskinesia and the 3-year course of schizophrenia: results from a large, prospective, naturalistic study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(10):1580-1588. 5. Caroff SN, Davis VG, Miller DD, et al; CATIE Investigators. Treatment outcomes of patients with tardive dyskinesia and chronic schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(3):295-303. 6. American Psychiatric Association. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2021. 7. AUSTEDO® XR (deutetrabenazine) extended-release tablets/AUSTEDO® current Prescribing Information. Parsippany, NJ: Teva Neuroscience, Inc. 8. Chow SC. Bioavailability and bioequivalence in drug development. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Stat. 2014;6(4):304-312. 9. Data on file. Teva Neuroscience, Inc. 10. Anderson KE, Stamler D, Davis MD, et al. Deutetrabenazine for treatment of involuntary movements in patients with tardive dyskinesia (AIM-TD): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(8):595-604. 11. Fernandez HH, Factor SA, Hauser RA, et al. Randomized controlled trial of deutetrabenazine for tardive dyskinesia: the ARM-TD study. Neurology. 2017;88(21):2003-2010. 12. Hauser RA, Barkay H, Fernandez HH, et al. Long-term deutetrabenazine treatment for tardive dyskinesia is associated with sustained benefits and safety: a 3-year, open-label extension study. Front Neurol. 2022;13:773999. 13. Ingrezza® (valbenazine) capsules. Prescribing Information. San Diego, CA: Neurocrine Biosciences, Inc.

IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION

Indications and Usage

AUSTEDO® XR (deutetrabenazine) extended-release tablets and AUSTEDO® (deutetrabenazine) tablets are indicated in adults for the treatment of chorea associated with Huntington's disease and for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia.

Important Safety Information

Depression and Suicidality in Patients with Huntington's Disease: AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO can increase the risk of depression and suicidal thoughts and behavior (suicidality) in patients with Huntington's disease. Balance the risks of depression and suicidality with the clinical need for treatment of chorea. Closely monitor patients for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidality, or unusual changes in behavior. Inform patients, their caregivers, and families of the risk of depression and suicidality and instruct them to report behaviors of concern promptly to the treating physician. Exercise caution when treating patients with a history of depression or prior suicide attempts or ideation. AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO are contraindicated in patients who are suicidal, and in patients with untreated or inadequately treated depression.

Contraindications: AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO are contraindicated in patients with Huntington's disease who are suicidal, or have untreated or inadequately treated depression. AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO are also contraindicated in: patients with hepatic impairment; patients taking reserpine or within 20 days of discontinuing reserpine; patients taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), or within 14 days of discontinuing MAOI therapy; and patients taking tetrabenazine or valbenazine.

Clinical Worsening and Adverse Events in Patients with Huntington's Disease: AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO may cause a worsening in mood, cognition, rigidity, and functional capacity. Prescribers should periodically re-evaluate the need for AUSTEDO XR or AUSTEDO in their patients by assessing the effect on chorea and possible adverse effects.

QTc Prolongation: AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO may prolong the QT interval, but the degree of QT prolongation is not clinically significant when AUSTEDO XR or AUSTEDO is administered within the recommended dosage range. AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO should be avoided in patients with congenital long QT syndrome and in patients with a history of cardiac arrhythmias.

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS), a potentially fatal symptom complex reported in association with drugs that reduce dopaminergic transmission, has been observed in patients receiving tetrabenazine. The risk may be increased by concomitant use of dopamine antagonists or antipsychotics. The management of NMS should include immediate discontinuation of AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO; intensive symptomatic treatment and medical monitoring; and treatment of any concomitant serious medical problems.

Akathisia, Agitation, and Restlessness: AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO may increase the risk of akathisia, agitation, and restlessness. The risk of akathisia may be increased by concomitant use of dopamine antagonists or antipsychotics. If a patient develops akathisia, the AUSTEDO XR or AUSTEDO dose should be reduced; some patients may require discontinuation of therapy.

Parkinsonism: AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO may cause parkinsonism in patients with Huntington's disease or tardive dyskinesia. Parkinsonism has also been observed with other VMAT2 inhibitors. The risk of parkinsonism may be increased by concomitant use of dopamine antagonists or antipsychotics. If a patient develops parkinsonism, the AUSTEDO XR or AUSTEDO dose should be reduced; some patients may require discontinuation of therapy.

Sedation and Somnolence: Sedation is a common dose-limiting adverse reaction of AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO. Patients should not perform activities requiring mental alertness, such as operating a motor vehicle or hazardous machinery, until they are on a maintenance dose of AUSTEDO XR or AUSTEDO and know how the drug affects them. Concomitant use of alcohol or other sedating drugs may have additive effects and worsen sedation and somnolence.

Hyperprolactinemia: Tetrabenazine elevates serum prolactin concentrations in humans. If there is a clinical suspicion of symptomatic hyperprolactinemia, appropriate laboratory testing should be done and consideration should be given to discontinuation of AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO.

Binding to Melanin-Containing Tissues: Deutetrabenazine or its metabolites bind to melanin-containing tissues and could accumulate in these tissues over time. Prescribers should be aware of the possibility of long-term ophthalmologic effects.

Common Adverse Reactions: The most common adverse reactions for AUSTEDO (>8% and greater than placebo) in a controlled clinical study in patients with Huntington's disease were somnolence, diarrhea, dry mouth, and fatigue. The most common adverse reactions for AUSTEDO (4% and greater than placebo) in controlled clinical studies in patients with tardive dyskinesia were nasopharyngitis and insomnia. Adverse reactions with AUSTEDO XR extended-release tablets are expected to be similar to AUSTEDO tablets.

Please see accompanying full Prescribing Information, including Boxed Warning.

Floresville, Texas

This interview with a prominent thought leader in psychiatry is about the role nurse practitioners (NPs) play in the management of tardive dyskinesia (TD) and examines what once-daily AUSTEDO XR tablets could mean for NPs and their patients.

Q:What is the role of advanced practice providers, specifically NPs, in psychiatry and the care they provide to patients with TD?

A:The role of the NP in psychiatry was developed many years ago to serve as an extension of the psychiatrist and fill in the gaps in mental healthcare. However, over the past 10 years, the role has expanded as NPs have made up an increasing proportion of healthcare professionals (HCPs) in psychiatry and see a much larger population of patients than ever before.

Psychiatric NPs are trained on the holistic model of care, which takes the whole patient into consideration. This means we consider not just their mental health but also, for example, their financial stability, socioeconomic status, and living situation to make decisions on how to best communicate with the patient, make a diagnosis, and choose an appropriate treatment strategy for each patient.

Our goal is to take care of our patients with mental health disorders, and very often, we treat them with antipsychotic drugs (APDs). Knowing that this type of treatment may lead to TD, it is our job to understand the risk of TD in patients, recognize TD movements when they occur, and then manage the treatment of it.

Q:Do you believe that the standard of care is being met for the average patient with TD?

A:TD continues to be underdiagnosed and undertreated, so I don't think the standard of care is being upheld for all patients with TD. It is important to screen for and assess movements in all patients taking APDs at every visit. Some providers find it challenging to do this because they overestimate the time it takes, but I try to explain to my colleagues that it really only takes a few minutes. I ask patients if they have ever noticed having any unusual movements while they've been on APDs. I inform them that this is something that can happen over time and that I'm going to ask them about it every time I see them.

It's also important to make patients active participants in their care by educating them about the risk of TD associated with APDs and empowering them to recognize possible TD-related movements. If my patient reports movements or I recognize them during an office visit, then we can discuss appropriate treatment.

Q:How do you differentiate TD from drug-induced parkinsonism (DIP)? What do you look for in a differential diagnosis?

A:DIP and TD are similar in that they both involve dopamine, but other than that, they're very different.

DIP is a hypokinetic disorder, which comes from blocking dopamine receptors and reducing dopamine signaling in the brain. I explain to patients that it is like being the Tin Man from The Wizard of Oz: movements are reduced overall, and it is associated with stiffness and rigidity. If there are abnormal movements, they usually present as rhythmic tremors in the hand. If you don't see them in the hand, you might notice them in the center of the lips or the corners of the mouth.

In contrast, TD is a hyperkinetic disorder. I tell patients that it's like driving a car on the Autobahn at 105 miles per hour: movements are fast and irregular.

Another way to distinguish DIP from TD is to ask a patient to walk. Patients with TD don't typically show any walking issues, but patients with DIP do. You may notice patients with DIP are hunched over, walk with a wide-stance, and turn with small shuffling steps even when walking straight. Also, DIP symptoms may sometimes be more prominent on one side of the body than the other.

Those are the distinguishing features that I look for when I'm trying to differentiate TD from DIP. I want to make sure to get it right because the treatment for one disorder can make the other one worse.

Q:We know that TD can impact various aspects of patients' lives, regardless of the severity of movements. What do you look for when you assess the impact of TD on patients, and how do you uncover the impact of TD on their lives?

A:Understanding impact is probably one of the most important aspects of managing patients with TD. This movement disorder impacts patients' lives in many different areas and can go beyond the severity as defined by the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) score.

To uncover the impact of TD, I ask the patient, or their caregiver if present, about how TD impacts them physically. Do they slur when they speak because of uncontrollable tongue movements? Do they unintentionally bite their tongue, get ulcerations in their mouth, or have any trouble swallowing? I've seen patients with movements in their upper extremities, which can make it difficult for them to hold utensils and cut food. Truncal movements can cause instability, leading to imbalance and falls. Moreover, many of my patients also have muscle discomfort because of their movements.

It's also important to ask about the impact of TD on patients' social lives. TD is a disorder of isolation. Patients may withdraw from their friends or family. They may stop going out and doing things they really enjoy because they are afraid of what other people might say. “What happens if somebody asks me about my movements? What if I'm an embarrassment to my family or friends or even to myself?”

It's critical to note here that TD can also impact my ability to help manage the patient's underlying mental health disorder.

Q:How does the impact of TD inform or drive treatment discussions with patients?

A:For me, impact is a key element in the decision to treat TD. The AIMS exam lays a solid foundation, but it's the impact that TD has on patients that really drives the decision.

It's also a key driver for talking to my patients about TD and motivating them to accept treatment. I ask patients to consider things that they've stopped doing or have difficulty doing because of their TD. In some cases, patients have had TD for so long that they've adapted to it and don't recognize the impact it is having until you ask them about things they are missing. Then, I ask patients to think about their lives and if those activities were less difficult. Patients will often accept treatment because they want to live a life with fewer TD symptoms.

A patient with chronic depression, who is a prominent lawyer, came to me after seeing multiple providers. She had been taking a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and a small dose of an atypical antipsychotic to manage her depression. She says it's worked many years for her to treat her depression. She said, “If I had to do it over again, I would continue on this treatment regimen.”

However, she began experiencing tongue movements that she recognized as a medication-related movement disorder. When she sought help from her previous providers, they either suggested changing her medication, which she didn't want to do, or advised her to wait since her symptoms were not severe enough to treat at the time.

Frustrated and unable to continue her job due to the impact of the movements, she came to me seeking assistance with Family Medical Leave Act paperwork. After assessing her using the AIMS and discussing the impact of her movements, it became clear that despite showing mild symptoms, the disorder significantly impacted her professional and social life. Her clients were choosing other lawyers to represent them, assuming her slurred speech indicated some type of impairment, and she faced contempt of court accusations due to her perceived mumbling or chewing in the courtroom. Socially, she was shunned by her colleagues and withdrew from attending her children's sporting events out of embarrassment.

Understanding the impact on her career and social interactions, I informed her about the American Psychiatric Association (APA) guidelines that recommend considering treatment for mild TD if it has an impact on the patient. I explained that if TD was affecting the patient's life, as hers was, and they preferred treatment, it should be considered. In line with these guidelines, we discussed a vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitor to address her symptoms.

Q:When starting a patient with TD on a VMAT2 inhibitor, how do you set expectations regarding the need to stay on therapy?

A:When starting a patient on a VMAT2 inhibitor, I discuss 3 important things: First, I educate the patient about the chronic and irreversible nature of TD. It is important for the patient to understand that, to maintain long-term control of the movements, they must stay on therapy, potentially for the rest of their lives.

Second, I explain the mechanism of action in simple terms. Uncontrollable movements are caused by excess dopamine signaling. VMAT2 inhibitors help to reduce that excess dopamine signaling and control movements.

And third, I talk about titration. With VMAT2 inhibitors like AUSTEDO XR, it is important to continue increasing the dose until symptoms are tolerably controlled.

Q:What do you think are the important clinical features of AUSTEDO XR as a once-daily treatment for adults with TD?

A:AUSTEDO XR offers patients the ability to take their medication once a day, at any time of the day, with or without food. Those are important features because many of my patients have preferences for when they take their medications, and this can help patients fit their TD treatment into their daily lives.

It's important to note that AUSTEDO XR is bioequivalent to the AUSTEDO® (deutetrabenazine) tablets BID formulation, and that means it can be considered therapeutically equivalent. Given the side effect profile established in the clinical trials with AUSTEDO BID and the mean compliance rate demonstrated in the long-term study—nearly 90% at 3 years—NPs can feel confident in their expectations that AUSTEDO XR will provide similar results.

Q:How do you set patient expectations with regard to titration with AUSTEDO XR?

A:In psychiatry, what we typically do is start low and go slow, but that is not needed with a VMAT2 inhibitor like AUSTEDO XR. I set the expectation, as outlined in the label, that we will continue to increase the dose weekly until the patient and I agree that they have tolerable symptom control.

I typically start a patient on the 4-week sample titration pack, which brings the patient to 30 mg/day in the first 4 weeks.

I use the next month to fine-tune the dosing for my patient. I reevaluate the severity of the movements. I ask about impact. Together, the patient and I decide whether we think we can get additional improvement in symptoms by increasing the dose to 36 mg/day, and I emphasize the importance of adherence to this maintenance dose over time.

Q:What do you look for in patients over time to ensure that their TD is adequately managed, and how do you adjust treatment with AUSTEDO XR, if needed?

A:TD waxes and wanes, and so we may have to adjust the dosing based on that, but a nice thing about AUSTEDO XR is that we have 7 dosages to work with. We can adjust the dosage to meet the patient's needs as it relates to their TD movements.

Typically, I see the patient every 4 to 6 weeks, and at that time, I make sure they are remaining compliant and regularly taking their maintenance dose. I ask about movements and their impact. I want to make sure that the patient continues to have the symptom control they want.

Recommended Reading

American Psychiatric Association. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2021. AUSTEDO® XR (deutetrabenazine) extended-release tablets/AUSTEDO® current Prescribing Information. Parsippany, NJ: Teva Neuroscience, Inc. Cai A, Mehrotra A, Germack HD, Busch AB, Huskamp HA, Barnett ML. Trends in mental health care delivery by psychiatrists and nurse practitioners in Medicare, 2011-19. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(9):1222-1230. Caroff SN, Citrome L, Meyer J, et al. A modified Delphi consensus study of the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of tardive dyskinesia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(2):19cs12983. Chow SC. Bioavailability and bioequivalence in drug development. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Stat. 2014;6(4):304-312. Cloud LJ, Zutshi D, Factor SA. Tardive dyskinesia: therapeutic options for an increasingly common disorder. Neurotherapeutics. 2014;11(1):166-176. Hauser RA, Meyer JM, Factor SA, et al. Differentiating tardive dyskinesia: a video-based review of antipsychotic-induced movement disorders in clinical practice. CNS Spectr. 2022;27(2):208-217. Jackson R, Brams MN, Citrome L, et al. Assessment of the impact of tardive dyskinesia in clinical practice: consensus panel recommendations. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:1589-1597. Jain R, Ayyagari R, Goldschmidt D, Zhou M, Finkbeiner S, Leo S. Impact of tardive dyskinesia on physical, psychological, social, and professional domains of patient lives: a survey of patients in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2023;84(3):22m14694. Ward KM, Citrome L. Antipsychotic-related movement disorders: drug-induced parkinsonism vs. tardive dyskinesia—key differences in pathophysiology and clinical management. Neurol Ther. 2018;7(2):233-248. Zutshi D, Cloud LJ, Factor SA. Tardive syndromes are rarely reversible after discontinuing dopamine receptor blocking agents: experience from a university-based movement disorder clinic. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y). 2014;4:266.