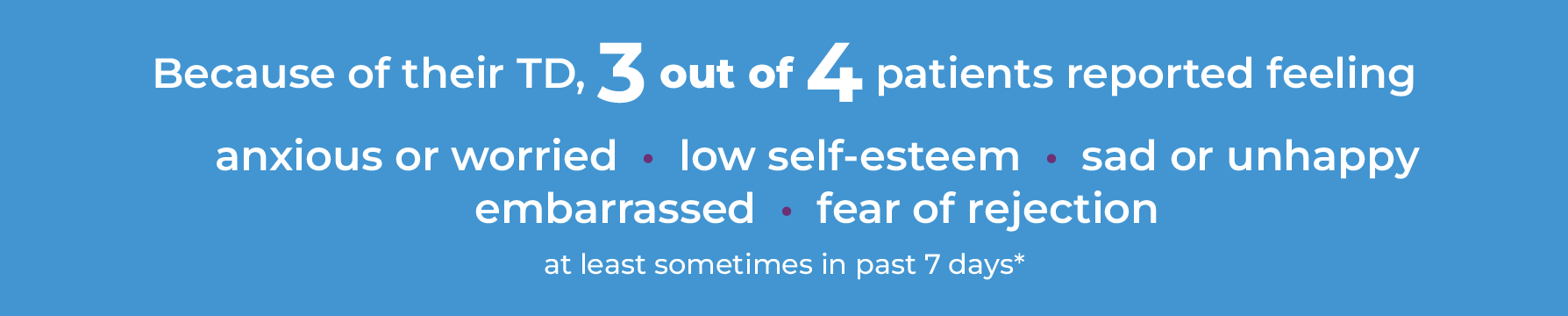

TD is a persistent, typically irreversible, involuntary movement disorder associated with prolonged exposure to antipsychotic drugs (APDs).1-3 TD can substantially impact many aspects of patients' lives, including their ability to perform daily activities, be productive, and socialize.3-5 The impact of TD was assessed in a recent online survey of 269 patients with TD and found that 3 out of 4 patients reported a severe impact of TD on their daily lives, leading to functional disability through its impact on the psychological, social, physical, and vocational domains of patients' lives.6,7 To address the issue, a consensus panel consisting of 9 healthcare professionals with expertise in TD recently developed the Impact-TD scale to help providers assess the impact of TD on patients' daily functioning.7

TD can also have an impact on caregivers. According to a survey, nearly 1 in 4 caregivers reported severe impact of the patient's TD on their own functioning and well-being.8

According to the results of a recent survey of 269 patients with TD, up to 85% of patients with TD reported negative psychological/psychiatric consequences of TD.6,9 In addition, more than 39% of patients with TD reported that they skipped, reduced, or stopped taking their APD.6

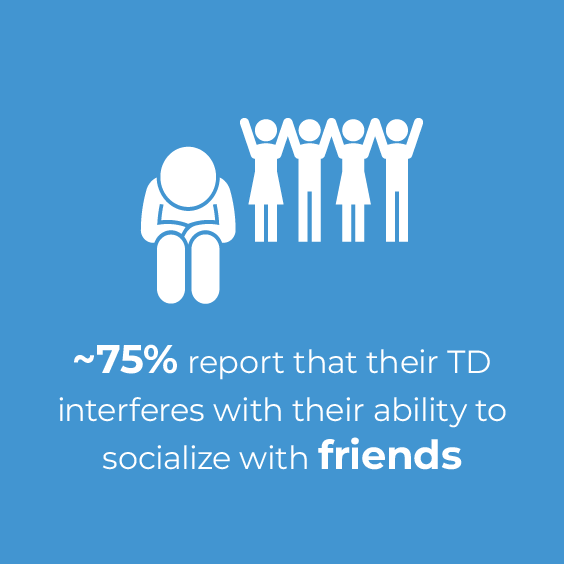

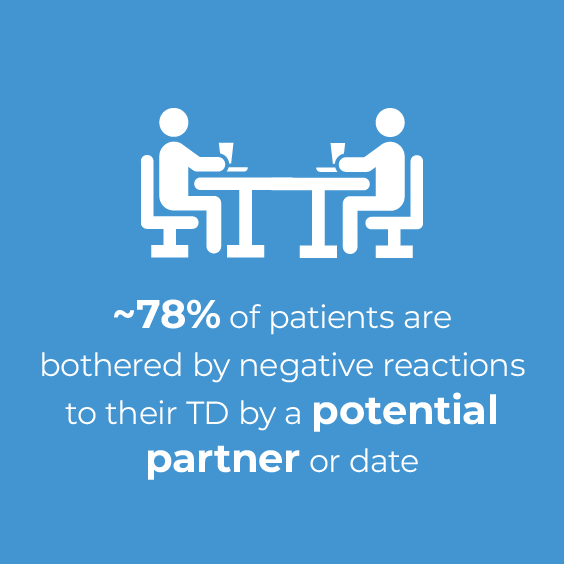

TD can have a substantial effect on patients' social interactions, including reduced romantic relationships, reduced friendships, and increased social avoidance and withdrawal.10,11 According to the results of an online survey, over three-quarters of patients reported a social impact of TD on their day-to-day activities, up to 75% of patients reported that TD interferes with their ability to socialize with friends, and 78% of patients were bothered by negative reactions to their TD by a potential partner or date.9

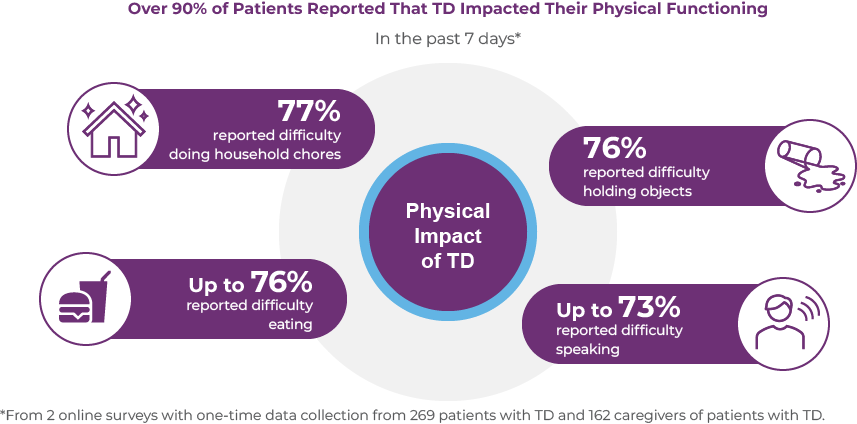

The symptoms of TD can lead to complications that may impact the physical well-being of patients with TD. These complications include dental damage, biting of lips and tongue, spilling food/difficulty eating, and musculoskeletal pain or discomfort.11-13 In 2 recent online surveys of 269 patients with TD and 162 caregivers, over 90% of patients reported that TD impacted their physical functioning.14 Moreover, 70% of patients with TD reported that their condition caused them pain.14 As shown in the figure below, in the past 7 days, 77% of patients with TD reported difficulty doing household chores, up to 76% had difficulty eating, 76% had difficulty holding objects, and up to 74% had difficulty speaking.14

The impact of TD can spread to employment, education, and recreation of patients with TD, who reported reduced work productivity and activity impairment, missed job opportunities, missed opportunities for promotion and/or new responsibilities, and missed educational opportunities.4,7,15 In 2 recent online surveys of 269 patients with TD and 162 caregivers, 73% of patients reported that TD impacted their ability to work because of speech difficulties.14 Additionally, nearly 1 in 3 patients (31.6%) reported that TD prevented them from pursuing or continuing education.9,15

Supporting patients with TD can have an impact on caregivers' own activities and well-being.8 Caregivers reported impairment at work, including missed workdays and difficulty while working, feeling anxious or worried about the patient in their care, and less enjoyment from being with friends.8 In a recent survey of 162 unpaid caregivers of patients with TD, nearly 1 in 4 caregivers (23.5%) reported that TD had a significant impact on their own functioning and well-being.8

A consensus panel of independent experts in psychiatry and movement disorder neurology with clinical and/or research experience in TD convened to develop recommendations on the importance of key elements in assessing the impact of TD on patients' functioning that can be used in clinical practice.4 Recommendations were developed for 6 key topics: diagnosis of TD, importance of assessing the impact of TD, key domains for assessing the impact of TD, time points for assessing the impact of TD, approaches to assessing the impact of TD, and initiating treatment of TD.4

The consensus panel recommendations4:

| • | Assessment of impact should be performed at every patient visit |

| • | Shared decision to treat TD must consider impact |

The routine assessment of TD in clinical practice is often lacking, despite its potential to profoundly impact patients' lives.4 To address this gap, a consensus panel of clinicians with experience in treating TD and/or conducting TD research, supported by an unrestricted grant from Teva, developed the Impact-TD scale.7 The goal of the Impact-TD scale is to provide a short, easy-to-administer checklist to facilitate the assessment of TD impact in clinical practice by a variety of providers. This tool provides questions that can be used to assess the functional impact of TD across 4 domains: psychological/psychiatric, social, physical, and vocational/educational/recreational.7 The Impact-TD scale includes severity score assessments for each domain.7 The impact score ranges from 0 (no impact) to 3 (significant and detrimental impact). To determine the score, the degree of interference, distress, and/or frequency for each domain is considered.7 The global Impact-TD score is based on the highest single score for any domain.7 The Impact-TD scale can be used to document changes in the impact of TD over time or with treatment.7

Provide a short, easy-to-administer checklist to facilitate the assessment of TD impact in clinical practice by a variety of providers

For more about the scale developed by the consensus panel,

download the full reprint

It is important to consider the impact of TD when making treatment decisions. Even small movements associated with TD can have a significant impact on the patient's daily life, which is why the American Psychiatric Association (APA) guidelines recommend appropriate treatment for TD if it has an impact on the patient, regardless of severity.4,16,17 The APA guidelines recommend that moderate to severe or disabling TD should be treated with a vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 (VMAT2) inhibitor and that mild TD should be considered for treatment if it has an impact on the patient.17

Overall, TD can substantially impact many aspects of patients' lives, including their ability to perform daily activities, be productive, and socialize.3-5 A survey found that 3 out of 4 patients reported a severe impact of TD on their daily lives, leading to functional disability.6 TD causes disability through its impact on the psychological, social, physical, and vocational domains of patients' lives.7 Supporting patients with TD can have an impact on caregivers' own activities and well-being.8 However, the routine assessment of TD in clinical practice is often lacking, despite its potential to profoundly impact patients' lives.4 A consensus panel of independent experts in psychiatry and movement disorder neurology with clinical and/or research experience in TD recommend that assessment of impact should be performed at every patient visit and that the shared decision to treat TD must consider impact.4 The Impact-TD scale was created to assess the functional impact of TD across 4 domains that include psychological, social, physical, and vocational.7 The Impact-TD scale can be used to document changes in the impact of TD over time or with treatment.7 The APA guidelines recommend that moderate to severe or disabling TD should be treated with a VMAT2 inhibitor and that mild TD should be considered for treatment if it has an impact on the patient.17

References

MHDs can be severe and persistent, and disorders such as TD that may develop due to prolonged use of APDs used to treat the underlying MHD can also be long-term and substantially impact daily functioning.3-5 APDs can be used to treat many MHDs, including schizophrenia, depression, and bipolar disorder. These disorders are long-term and impair patient functioning, with most requiring lifelong treatment.6-9 Up to 20% to 30% of patients treated with typical or atypical APDs are at risk for developing TD, a chronic and disabling hyperkinetic movement disorder characterized by involuntary movements in any part of the body, but typically the orofacial region.10,11 Most cases of TD may develop over months to years, with some patients experiencing symptoms even after 10 years.12,13 TD is typically irreversible, with symptoms persisting even after discontinuation of the APD.14,15

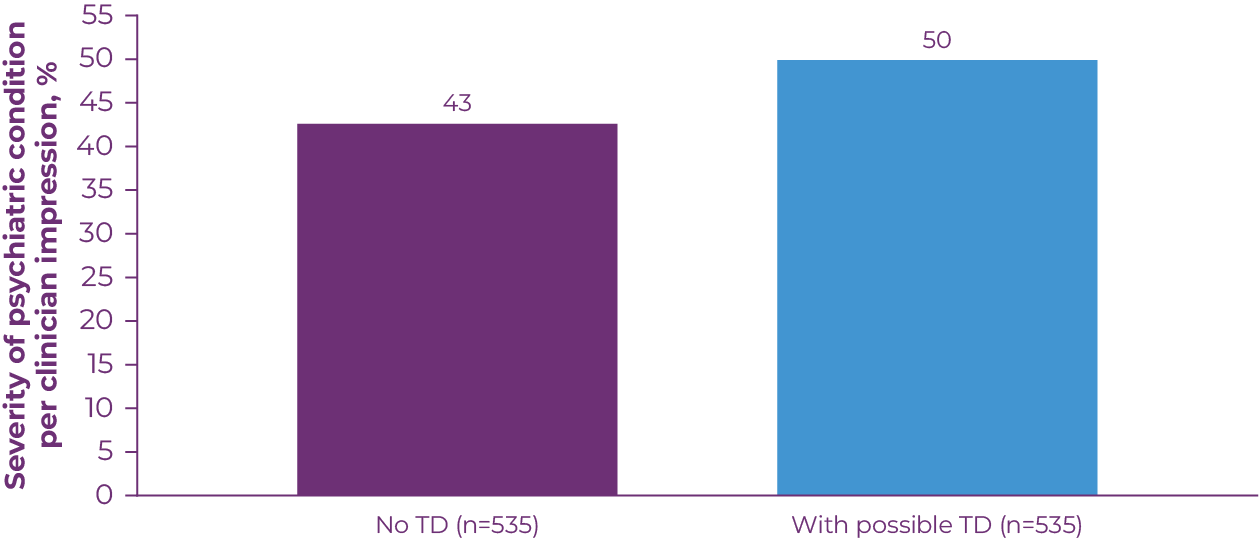

TD symptoms can be distressing in patients with mood disorders, a population generally more aware of their movements.16 The presence of TD is associated with worse health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and social withdrawal, with the most severe impacts on physical aspects of functioning.17 In a 2020 study that assessed the impact of TD in antipsychotic-treated patients, 50% of patients with possible TD had a moderate to severe psychiatric condition, compared with 43% of patients without possible TD (Figure 2.1).18

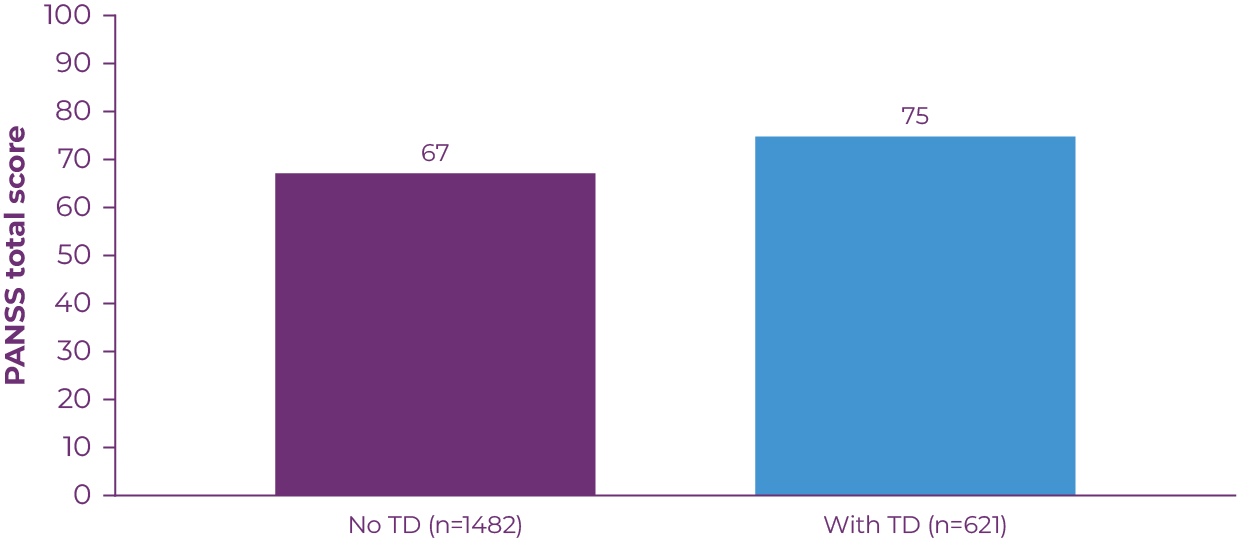

In patients with schizophrenia, TD has been associated with poor response to treatment, greater risk of relapse, lower quality of life and functioning, and higher mortality.19 A 3-year prospective study involving patients with schizophrenia demonstrated that TD is associated with poor response to treatment. Patients with TD had more severe schizophrenic symptoms, as measured by total score on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Figure 2.2).13 TD may also aggravate existing issues with self-stigma and social withdrawal, and increase feelings of paranoia or psychosis related to a patient's underlying condition.20

TD impacts psychiatric symptoms as well as adherence to the APD, which is required to maintain long-term stability of the underlying MHD.20-22 Many chronic illnesses, including schizophrenia and major depressive disorder, have high rates of nonadherence.23 At least two-thirds of patients with schizophrenia are partially nonadherent to their medication.24 There could be many reasons for nonadherence, including substance abuse, social isolation, and cognitive impairment.25 A strong alliance between the clinician and patient can greatly improve adherence rates and the likelihood of receiving benefits from the medication.26 However, the presence of TD may impact a patient's adherence to their APD. An online survey of 269 patients with TD assessed the patient-reported 7-day impact of TD on various aspects of daily life. The study found that 48% reported skipping doses of APD or taking less than instructed, 39% reported stopping the medication altogether, 36% stopped visits to the doctor treating their underlying condition, and 21% advised someone else not to take the medication (Figure 2.3).6 The impact of TD on a patient's adherence to the APD makes it more challenging for the clinician to treat the patient's underlying MHD.

All patients taking APDs are at risk of developing TD, which is chronic, typically irreversible, and often underdiagnosed.2,3,27 However, implementing formal screening protocols may be perceived as a challenge for clinicians. APA guidelines and expert opinion recommend that all patients with APDs should be assessed for movements at every clinical encounter. This can be accomplished through a combination of structured assessments, such as the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS), and semistructured assessments.3,28,29

It is also important to assess the impact of TD on daily functioning when making treatment decisions. The Impact-TD scale is an easy-to-use checklist developed by a consensus panel of clinicians with experience in treating TD and/or conducting TD research that examines impact of TD across 4 functional domains of patients' lives: psychological/psychiatric, social, physical, and vocational/educational/recreational. It may be useful in assessing the impact of TD to improve patient outcomes. Understanding the burden of TD on patients is an important aspect of long-term management, as it can vary over time and affect treatment decisions. Even patients with mild TD may experience a significant functional impact of TD on their daily lives.20,29 Being aware of the available tools and how to use them can ensure that all patients taking APDs are adequately assessed and that TD can be appropriately treated when it is detected.

The clinical approach to managing TD has typically focused on dose reduction or discontinuation of the APD.30,31 However, this may not improve TD symptoms, and multiple studies have demonstrated that TD may be irreversible despite APD discontinuation.14,15 Additionally, it may not be practical to modify the dose of an APD for a patient if the medication significantly benefits daily functioning.10 APA guidelines recommend treating TD appropriately if it has an impact on the patient, regardless of severity. Moderate to severe or disabling TD should be treated with a vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitor. Mild TD should be considered for treatment if it has an impact on the patient. VMAT2 inhibitors can be administered without the need to change the dose of the APD. VMAT2 inhibitors can be considered as a treatment option for TD so the provider can focus on maintaining stability of the underlying MHD.28

References

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) guidelines recommend vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors, such as AUSTEDO XR, as a first-line treatment option for tardive dyskinesia (TD). This article explores key findings from the clinical trials with the AUSTEDO BID formulation, including symptom control, long-term results, and safety profile. It also examines dosing options for AUSTEDO XR, emphasizing the ability to treat TD without disrupting the current antipsychotic medication regimen or undermining mental health stability.

TD is a persistent, often irreversible, hyperkinetic movement disorder resulting from chronic exposure to dopamine receptor blocking agents (DRBAs), including antipsychotic drugs (APDs).1-3 In the United States, TD affects approximately 785,000 patients.4 Unfortunately, TD may be underdiagnosed and undertreated, with approximately 15% of patients with TD receiving a formal diagnosis and less than 6% of patients being treated with VMAT2 inhibitors.4 TD can have a profound impact on patients' lives and complicate management of their mental health disorders.5 The APA guidelines recommend that moderate to severe or disabling TD should be treated with a VMAT2 inhibitor and that mild TD should be considered for treatment if it has an impact on the patient.6 Once-daily AUSTEDO XR is a VMAT2 inhibitor approved in adults for the treatment of TD.7

Bioequivalence of AUSTEDO XR to AUSTEDO BID was established based on pharmacokinetic profile studies performed across 3 phase 1 clinical trials in healthy volunteers.4 Data support bioequivalence of AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO BID across the full clinical dosing range (12 mg once daily [QD] to 48 mg QD).4 When 2 formulations are shown to be bioequivalent, they can be considered therapeutically equivalent.8

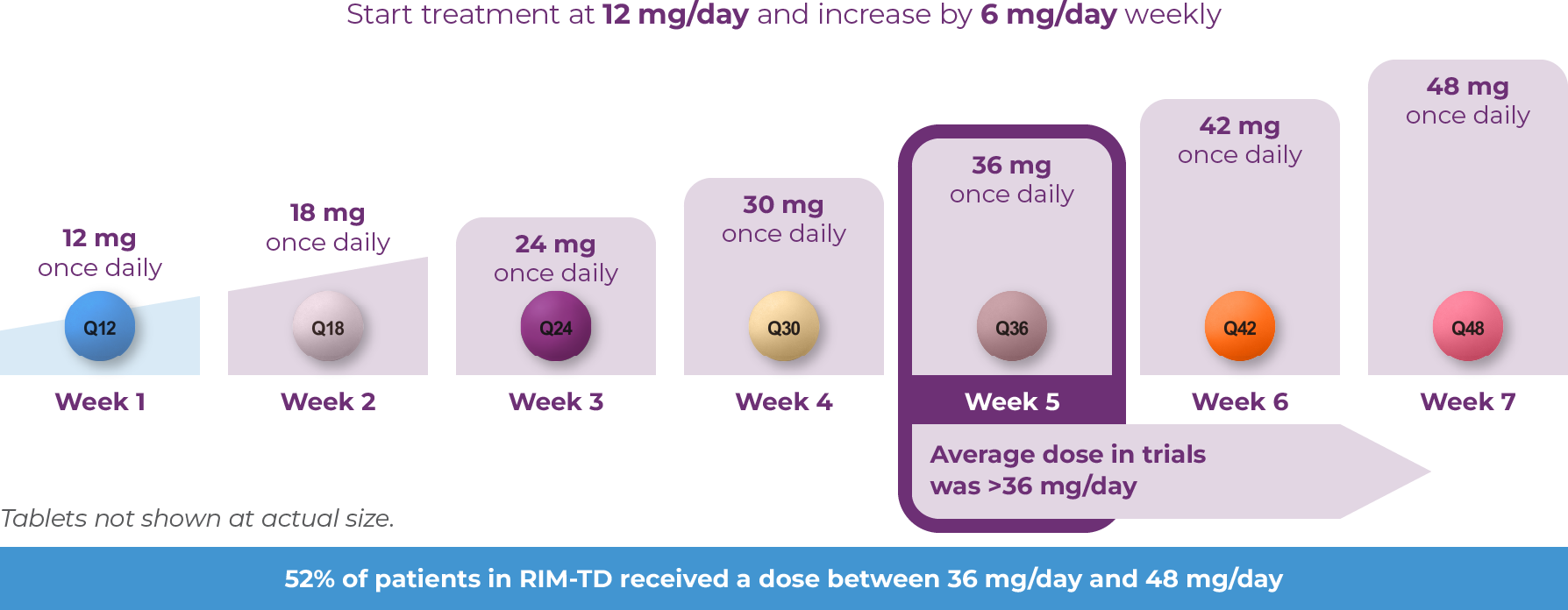

The efficacy and safety profile of AUSTEDO was established in 2 pivotal clinical trials, ARM-TD (Aim to Reduce Movements in Tardive Dyskinesia) and AIM-TD (Addressing Involuntary Movements in Tardive Dyskinesia).9,10 Patients in these trials received the AUSTEDO BID formulation. ARM-TD was a flexible-dose clinical trial in which treatment was titrated to an individualized dose that reduced abnormal movements and was tolerated.7,9,10 Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive AUSTEDO or placebo. The starting dose of AUSTEDO was 12 mg/day, which was increased by 6 mg/day each week until satisfactory dyskinesia control was achieved, intolerable side effects occurred, or a maximal dose of 48 mg/day was reached. The 12-week treatment period included a 6-week titration period, during which patients were titrated to an optimal dose; a 6-week maintenance period; and a 1-week washout.7,10 AIM-TD was a fixed-dose trial in which patients were randomized 1:1:1:1 to 12 mg AUSTEDO, 24 mg AUSTEDO, 36 mg AUSTEDO, or placebo. The 12-week treatment period included a 4-week dose-escalation period and an 8-week maintenance period followed by a 1-week washout.7,10 The dose of AUSTEDO was started at 12 mg/day and increased in 6-mg/day increments each week to a target dose of 12 mg/day, 24 mg/day, or 36 mg/day.7,9 In both studies, most patients were on APDs; 64% of patients were receiving atypical antipsychotics while 12% were receiving typical or combination antipsychotics.7

The primary efficacy endpoint in both studies was the change in Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) total score (sum of items 1 through 7) from baseline (defined for each patient as the value from the day 0 visit) to Week 12, as assessed by 2 blinded central video ratings. Higher AIMS scores are indicative of more severe TD.4,7,9,10

Patients in the ARM-TD study showed a significant improvement in AIMS total score from baseline (P=0.019) at Week 12 vs placebo (3.0-point reduction vs 1.6-point reduction).4,10 The mean dose of AUSTEDO among all patients in the modified intention-to-treat population was 38.8 mg/day at the end of the 6-week titration period and 38.3 mg/day at the end of treatment.4

In AIM-TD, AUSTEDO significantly reduced AIMS total score by 3.3 points from baseline in the 36-mg/day arm (versus a reduction of 1.4 points with placebo) at Week 12 (P=0.001; treatment effect of -1.9 points).7,9 In an exploratory analysis, significant AIMS total score reduction was seen at 2 weeks for the 24-mg/day (95% CI, -2.41 to -0.41; P=0.006) and 36-mg/day groups (-1.1 points [0.49]; 95% CI, -2.04 to -0.10; P=0.032).9

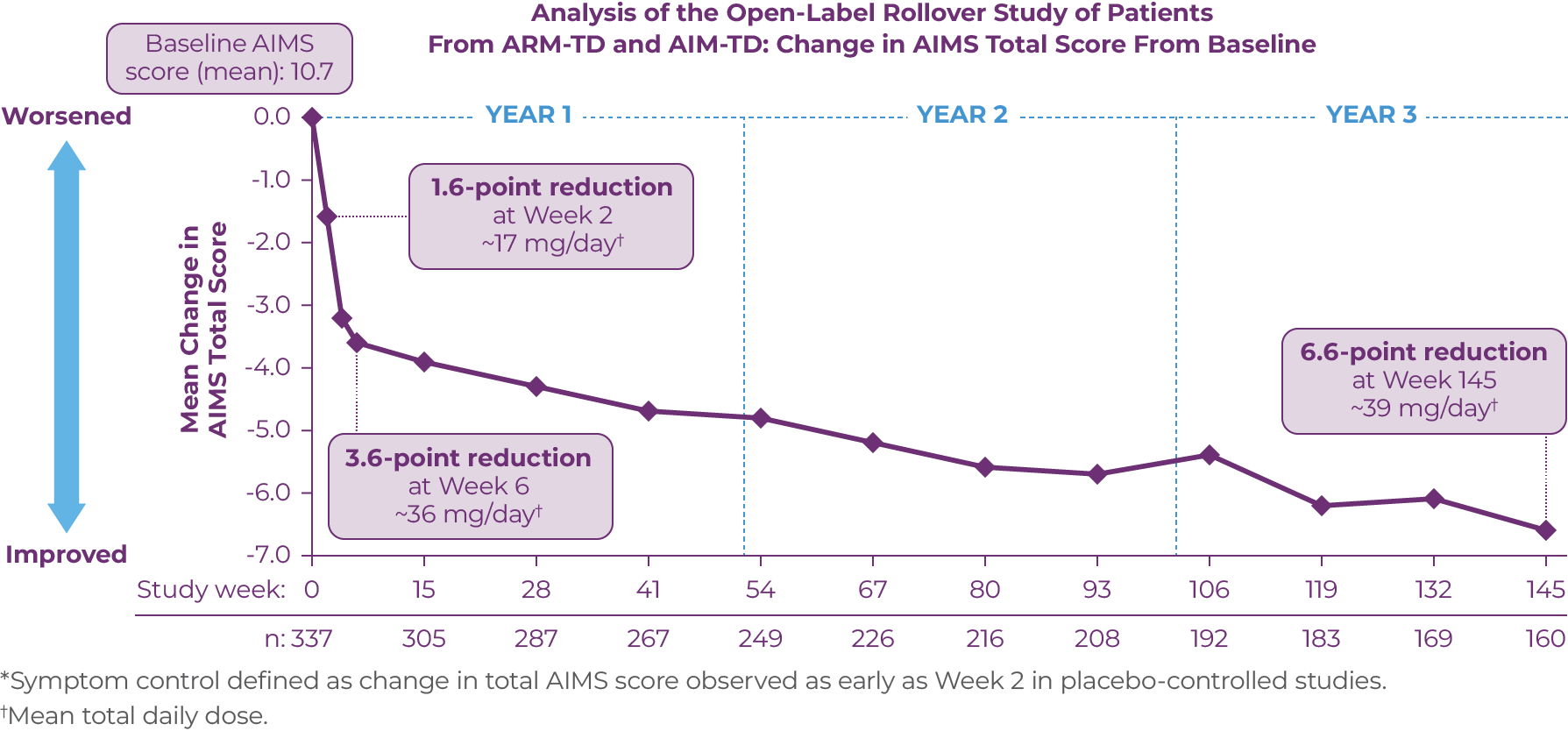

Given the chronic nature of TD, there is a need for long-term treatment.1,2 RIM-TD (Reducing Involuntary Movements in Participants With Tardive Dyskinesia) was an open-label, long-term maintenance study in patients who successfully completed ARM-TD or AIM-TD.11 Patients in the RIM-TD trial received the AUSTEDO BID formulation. Patients discontinued AUSTEDO for 1 week and then started at a dose of 12 mg/day, which was titrated for up to 6 weeks.11 The dose was increased in a response-driven manner on a weekly basis by 6 mg/day until the maximum allowable dose was reached, a clinically significant adverse event (AE) occurred, or adequate dyskinesia control was achieved. Patients were followed for approximately 3 years.11

Among the patients evaluated, 337 patients had treatment at baseline and 160 patients had treatment through the end of Week 145. During the overall treatment period, patients generally experienced an improvement in AIMS total score. There was a gradual reduction in mean AIMS total score from baseline through Week 145 (Figure 3.1).11 The average dose of AUSTEDO was >36 mg/day (39.4 mg/day at Week 145).11

At Week 145 in RIM-TD, 67% of patients achieved ≥50% improvement in AIMS total score.11 Clinicians and patients generally recognized improvement in TD symptoms with AUSTEDO treatment based on assessments of Clinical Global Impression of Change and Patient Global Impression of Change over time.11 At Week 145, a majority of patients (63%) and physicians (73%) reported symptoms as “much improved” or “very much improved.”11 Preexisting psychiatric scores remained stable throughout the treatment period, and AEs were comparable to those seen in the clinical trials.4 The mean overall compliance rate was nearly 90% at 3 years.4

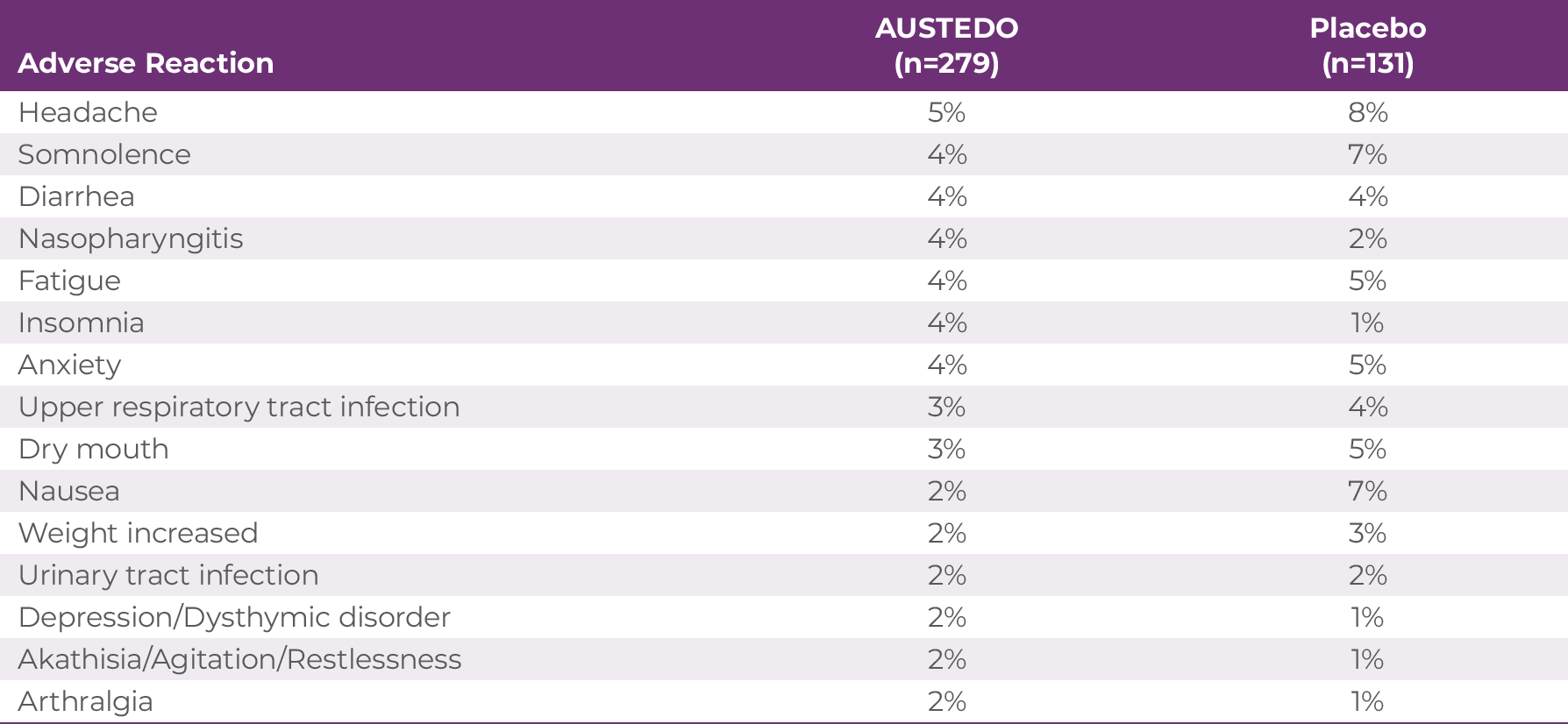

The most commonly reported AEs by patients treated with AUSTEDO (>3% and greater than placebo) in the placebo-controlled studies were nasopharyngitis and insomnia (Table 3.1).4 Discontinuation due to AEs occurred in 4% of patients taking AUSTEDO vs 3% of patients taking placebo.9 Dose reduction due to AEs was required in 4% of patients taking AUSTEDO vs 2% of patients taking placebo.7 Once patients were titrated to their maintenance dose, the following AEs were no longer reported: dry mouth, nausea, and hypertension in AIM-TD and somnolence and dry mouth in ARM-TD.4 Adverse reactions with AUSTEDO XR are expected to be similar to those with AUSTEDO BID.7

The safety profile from the RIM-TD 3-year study was comparable to the safety profiles from the 12-week clinical trials.10 There were no new safety signals identified in RIM-TD.10

AUSTEDO XR is metabolized primarily through CYP2D6, with minor contributions of CYP1A2 and CYP3A4/5, to form several minor metabolites.4 Metabolic pathways should be considered when choosing a treatment for TD.4 AUSTEDO XR has no recommendations against concomitant use with CYP3A4/5 inducers or inhibitors and should be considered for patients with TD receiving CYP3A4/5 inducers or inhibitors for their comorbidities.4

AUSTEDO XR is available in 12 mg, 18 mg, 24 mg, 30 mg, 36 mg, 42 mg, and 48 mg extended release tablets, providing flexibility for effective and tolerable symptom control.7 The starting dose for patients with TD is 12 mg/day. Clinicians can increase the dose of AUSTEDO XR by 6 mg/day at weekly intervals for individual patients based on their desired symptom control and tolerability (Figure 3.2).7 The average daily dose in clinical trials was >36 mg/day.8-10 Once-daily AUSTEDO XR may be taken at any time of day with or without food. AUSTEDO XR tablets should be swallowed whole and not chewed, crushed, or broken.4 The maximum recommended daily dosage of AUSTEDO XR is 48 mg.4 To get new patients started on AUSTEDO XR, a 4-week Titration Kit that brings patients to 30 mg/day within the first 4 weeks is available through sample or prescription.4 For continuing patients, once-daily AUSTEDO XR can be prescribed for their next refill at the same total daily dose as AUSTEDO BID.4

In the clinical studies with AUSTEDO BID, patients achieved rapid symptom control, defined as a change in total AIMS score, as early as Week 2 in the placebo-controlled studies.4 In the long-term study, sustained results were observed through 3 years.10 The most common AEs reported in the placebo-controlled studies were nasopharyngitis and insomnia, and no new safety signals were observed in the 3-year open-label extension study.4,10 Since bioequivalence has been established between AUSTEDO BID and AUSTEDO XR, these drugs can be considered therapeutically equivalent.4,7 AUSTEDO XR has no recommendations against concomitant use with CYP3A4/5 inducers or inhibitors.4 With AUSTEDO XR, patients have the opportunity to achieve tolerable symptom control over time without disrupting their current APD treatment regimen and undermining the stability of their underlying mental health disorder.4

1. Hauser RA, Meyer JM, Factor SA, et al. Differentiating tardive dyskinesia: a video-based review of antipsychotic-induced movement disorders in clinical practice. CNS Spectr. 2022;27(2):208-217. 2. Fahn S, Jankovic J, Hallett M, eds. Principles and Practice of Movement Disorders. 2nd ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2011. 3. Zutshi D, Cloud LJ, Factor SA. Tardive syndromes are rarely reversible after discontinuing dopamine receptor blocking agents: experience from a university-based movement disorder clinic. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y). 2014;4:266. 4. Data on file. Teva Neuroscience, Inc. 5. Jain R, Ayyagari R, Goldschmidt D, Zhou M, Finkbeiner S, Leo S. Impact of tardive dyskinesia on physical, psychological, social, and professional domains of patient lives: a survey of patients in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2023;84(3):22m14694. 6. American Psychiatric Association. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2021. 7. AUSTEDO® XR (deutetrabenazine) extended-release tablets/AUSTEDO® current Prescribing Information. Parsippany, NJ: Teva Neuroscience, Inc. 8. Chow SC. Bioavailability and bioequivalence in drug development. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Stat. 2014;6(4):304-312. 9. Anderson KE, Stamler D, Davis MD, et al. Deutetrabenazine for treatment of involuntary movements in patients with tardive dyskinesia (AIM-TD): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(8):595-604. 10. Fernandez HH, Factor SA, Hauser RA, et al. Randomized controlled trial of deutetrabenazine for tardive dyskinesia: the ARM-TD study. Neurology. 2017;88(21):2003-2010. 11. Hauser RA, Barkay H, Fernandez HH, et al. Long-term deutetrabenazine treatment for tardive dyskinesia is associated with sustained benefits and safety: a 3-year, open-label extension study. Front Neurol. 2022;13:773999.

IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION

Indications and Usage

AUSTEDO® XR (deutetrabenazine) extended-release tablets and AUSTEDO® (deutetrabenazine) tablets are indicated in adults for the treatment of chorea associated with Huntington's disease and for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia.

Important Safety Information

Depression and Suicidality in Patients with Huntington's Disease: AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO can increase the risk of depression and suicidal thoughts and behavior (suicidality) in patients with Huntington's disease. Balance the risks of depression and suicidality with the clinical need for treatment of chorea. Closely monitor patients for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidality, or unusual changes in behavior. Inform patients, their caregivers, and families of the risk of depression and suicidality and instruct them to report behaviors of concern promptly to the treating physician. Exercise caution when treating patients with a history of depression or prior suicide attempts or ideation. AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO are contraindicated in patients who are suicidal, and in patients with untreated or inadequately treated depression.

Contraindications: AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO are contraindicated in patients with Huntington's disease who are suicidal, or have untreated or inadequately treated depression. AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO are also contraindicated in: patients with hepatic impairment; patients taking reserpine or within 20 days of discontinuing reserpine; patients taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), or within 14 days of discontinuing MAOI therapy; and patients taking tetrabenazine or valbenazine.

Clinical Worsening and Adverse Events in Patients with Huntington's Disease: AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO may cause a worsening in mood, cognition, rigidity, and functional capacity. Prescribers should periodically re-evaluate the need for AUSTEDO XR or AUSTEDO in their patients by assessing the effect on chorea and possible adverse effects.

QTc Prolongation: AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO may prolong the QT interval, but the degree of QT prolongation is not clinically significant when AUSTEDO XR or AUSTEDO is administered within the recommended dosage range. AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO should be avoided in patients with congenital long QT syndrome and in patients with a history of cardiac arrhythmias.

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS), a potentially fatal symptom complex reported in association with drugs that reduce dopaminergic transmission, has been observed in patients receiving tetrabenazine. The risk may be increased by concomitant use of dopamine antagonists or antipsychotics. The management of NMS should include immediate discontinuation of AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO; intensive symptomatic treatment and medical monitoring; and treatment of any concomitant serious medical problems.

Akathisia, Agitation, and Restlessness: AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO may increase the risk of akathisia, agitation, and restlessness. The risk of akathisia may be increased by concomitant use of dopamine antagonists or antipsychotics. If a patient develops akathisia, the AUSTEDO XR or AUSTEDO dose should be reduced; some patients may require discontinuation of therapy.

Parkinsonism: AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO may cause parkinsonism in patients with Huntington's disease or tardive dyskinesia. Parkinsonism has also been observed with other VMAT2 inhibitors. The risk of parkinsonism may be increased by concomitant use of dopamine antagonists or antipsychotics. If a patient develops parkinsonism, the AUSTEDO XR or AUSTEDO dose should be reduced; some patients may require discontinuation of therapy.

Sedation and Somnolence: Sedation is a common dose-limiting adverse reaction of AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO. Patients should not perform activities requiring mental alertness, such as operating a motor vehicle or hazardous machinery, until they are on a maintenance dose of AUSTEDO XR or AUSTEDO and know how the drug affects them. Concomitant use of alcohol or other sedating drugs may have additive effects and worsen sedation and somnolence.

Hyperprolactinemia: Tetrabenazine elevates serum prolactin concentrations in humans. If there is a clinical suspicion of symptomatic hyperprolactinemia, appropriate laboratory testing should be done and consideration should be given to discontinuation of AUSTEDO XR and AUSTEDO.

Binding to Melanin-Containing Tissues: Deutetrabenazine or its metabolites bind to melanin-containing tissues and could accumulate in these tissues over time. Prescribers should be aware of the possibility of long-term ophthalmologic effects.

Common Adverse Reactions: The most common adverse reactions for AUSTEDO (>8% and greater than placebo) in a controlled clinical study in patients with Huntington's disease were somnolence, diarrhea, dry mouth, and fatigue. The most common adverse reactions for AUSTEDO (4% and greater than placebo) in controlled clinical studies in patients with tardive dyskinesia were nasopharyngitis and insomnia. Adverse reactions with AUSTEDO XR extended-release tablets are expected to be similar to AUSTEDO tablets.

Please see accompanying full Prescribing Information, including Boxed Warning.

Assistant Clinical Adjunct Professor, Psychiatry, University of Michigan

Neurobehavioral Medicine Group, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

In this interview, we spoke with a distinguished opinion leader in psychiatry. During this interview, he addressed the impact of tardive dyskinesia (TD) and how it influences the assessment and treatment of this drug-induced movement disorder.

Q:What challenges are associated with managing the underlying mental health disorder in patients who develop TD?

A:Treating the underlying mental health disorder may be more challenging when the patient also has TD. Data show that patients with TD are less likely to adhere to their prescribed medications or may even stop taking them altogether due to the presence of TD symptoms. These symptoms can cause significant impairments, leading to social avoidance, depression, anxiety, and potentially exacerbating psychosis.

Abnormal movements associated with TD can trigger paranoid-like symptoms in patients, such as the feeling of being watched, talked about, or followed. Additionally, studies have revealed that people without TD have a negative response toward individuals with TD, which patients can perceive and internalize. These negative perceptions can worsen psychotic symptoms and mood disturbances.

What this means is that when TD goes unnoticed, it may complicate the treatment of the primary disorder, making it more challenging to achieve positive outcomes.

Q:Can you elaborate on the broad range of effects that TD can have on patients' lives, regardless of the severity of their movements? Why is it crucial for providers to evaluate the impact of TD?

A:Traditionally, the focus has been on the severity of movements associated with TD, without considering how these movements affect the patient's day-to-day functioning.

However, the impact of TD on patients' lives can be significant, regardless of the severity of the movements. As such, it is crucial for healthcare professionals to assess this impact comprehensively.

Unlike other areas of mental health, in which patient interviews are common, TD evaluation often overlooks the potential impact of even mild movements on patients. It is important to recognize that what the clinician observes may not accurately reflect the patient's actual experience.

Particularly, patients with mood disorder may not have greater severity of movements, but the impact of even small movements may be significant. These patients tend to be more actively engaged in work, social activities, and recreational pursuits, which means TD can affect multiple areas of their lives.

Assessing the impact of TD requires creating a framework that allows patients to express the effects they are experiencing. Since each patient's experience is unique, considering multiple areas of impact becomes essential. For instance, hand movements may significantly affect patients who rely heavily on manual dexterity, while vocalizations can interfere with communication regardless of occupation.

Neglecting to assess the impact of TD may lead to missed opportunities for understanding the patient's perspective. By listening attentively to patients, clinicians can gather their valuable insights into how TD affects their lives. Systematically capturing the impact through a standardized assessment process is crucial to identify a broad range of effects.

Q:Recently, a consensus panel that you participated in provided recommendations for assessing the impact of TD. What are the most important takeaways for your fellow psychiatry providers?

A:The consensus panel was an advisory panel of experts in psychiatry and movement disorder neurology that was convened to develop consensus recommendations on assessment of the impact of TD on patients' functioning that can be used in clinical practice.

The following are the key points from the recommendations made by the consensus panel regarding the assessment of TD in clinical practice:

To reiterate, the most important points from the recommendations are that TD can be diagnosed based on observable movements, that any level of movement can confirm the diagnosis, and that the clinician should consider the degree of impact of TD on the patient's daily life when initiating treatment. Regular monitoring and early intervention are essential, and healthcare professionals must involve patients in assessing the impact and provide appropriate treatment options.

Q:What is the Impact-TD scale and how do you think it has affected the psychiatry community?

A:The Impact-TD scale, developed by the consensus panel, is a short, easy-to-administer checklist that can be used as a guide to examine impact in the psychological/psychiatric, social, physical, and vocational/educational/recreational domains of patients’ lives, providing a simple and comprehensive way to evaluate impact.

The Impact-TD scale provides examples of difficulties resulting from TD that can occur in each domain, allowing clinicians to focus on the areas where the patient experiences the most impact. Not every area may be affected, but there is often overlap among the impacted domains.

It is my belief that the emphasis on impact, rather than just the severity of movements, will lead to improvements in the care of patients with TD. Using the Impact-TD scale and discussing impact at every visit should ensure that it is not overlooked.

And I believe that the Impact-TD scale has started to do that—bring more awareness and discussion of the impact of TD among healthcare professionals. However, I think there is still a substantial need to increase the awareness around the impact that TD has on patients’ lives.

Q:How can the Impact-TD scale facilitate a routine assessment of the impact of TD?

A:The scale can be used by any clinician who sees the patient, including case managers, therapists, and pharmacists, to ensure comprehensive assessment.

The scale can be printed out and kept on hand for easy reference during assessments. A single printed reference document could include the AIMS assessment on one side and the Impact-TD scale on the other. Clinicians should remember that the score in each domain should be assessed based on the patient's self-reported impact on functioning, rather than solely relying on the severity of the movements.

Psychiatrists can also incorporate the impact TD scale into their daily practice by familiarizing themselves with the 4 domains of the scale: psychiatric symptoms, social symptoms, medical problems, and work/school/leisure activities. They don't need to cover every item on the scale but should focus on the domains relevant to the patient's movements and their impact.

Q:Does the Impact-TD scale have broader uses? How might it be used in clinical trials?

A:The Impact-TD scale could have broader uses, including its incorporation into clinical trials to assess its correlation with other measures and its ability to capture improvements beyond the severity of the movements themselves.

If supported by the results of clinical trials, the Impact-TD scale could be used by clinicians to monitor the effect of treatment on impact over time. Clinicians can subsequently make dose adjustments based on impact rather than on severity of movements alone. Increasing the dose until impact is adequately controlled would be recommended unless the patient experiences adverse events or reaches the maximum dose. At present, no clinical studies have provided an evaluation of the effects of treating TD on the impact of movements across the 4 domains.

Q:How do you think a greater understanding of the impact of TD, and a greater focus on its assessment, will change the standard of care for TD? What would be the implications of such a change for psychiatrists?

A:The current standard of care, established by the APA and expert consensus, highlights the need to screen for TD movements in all patients taking APDs at every clinical encounter using a combination of structured and semistructured assessments, but these assessments primarily focus on the severity of movements and don't adequately capture the impact of movements, if present, on day-to-day life. Currently, the lack of standardized measures for assessing impact of TD is a challenge, and the scale provides a much-needed tool in this regard.

I believe that the Impact-TD scale should be incorporated into the APA guidelines and serve as a valuable resource for assessing impact. By increasing awareness and visibility of the scale through educational programs, seminars, and professional organizations like the APA, we can help promote its adoption as a standard of care.

Recommended Reading

American Psychiatric Association. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2021. Dr Richard Jackson on Assessing and Monitoring TD Through Telepsychiatry. Video transcript. Psychiatry & Behavioral Health Learning Network. June 15, 2020. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/pcn/multimedia/dr-richard-jackson-assessing-and-monitoring-td-through-telepsychiatry Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Revised. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1976:534-537. Jackson R, Brams MN, Carlozzi NE, et al. Impact-Tardive Dyskinesia (Impact-TD) scale: a clinical tool to assess the impact of tardive dyskinesia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2022;84(1):22cs14563. Jackson R, Brams MN, Citrome L, et al. Assessment of the impact of tardive dyskinesia in clinical practice: consensus panel recommendations. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:1589-1597. Jain R, Ayyagari R, King S, et al. Impact of tardive dyskinesia on physical, psychological, and social aspects of patient lives: a survey of patients and caregivers in the United States. Poster presented at: Psych Congress 2021; October 29-November 1, 2021; San Antonio, Texas.